Gillard snubs UN on single parent welfare, The Australian (AAP), March 4, 2013 | PM’s pay to crack $500k as part of MP salary rise, Stephanie Peatling, The Sydney Morning Herald, June 13, 2013.

Former prime minister Julia Gillard defended her controversial changes which moved single parents off their pension and on to the unemployment benefit Newstart, but she accepted Newstart was “too low”.

“I am going to stand up for it as a decision of the government I led,” she told journalist Anne Summers in Melbourne on Tuesday night.

It was the second major interview Gillard had done in as many days explaining her prime ministership, its policies, her leadership battles with Kevin Rudd and issues around gender. Summers also interviewed her in Sydney on Monday night. Both sellout audiences were overwhelmingly supportive and mostly women.

~ Julia Gillard defends single parent benefit change, Gabrielle Chan, The Grauniad, October 1, 2013

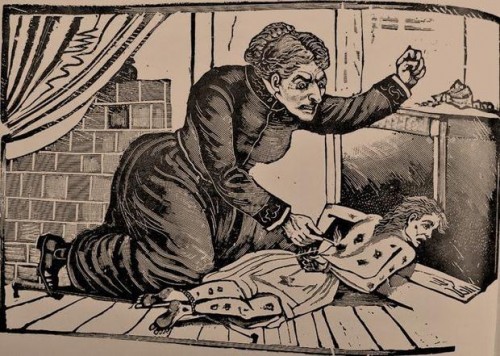

Sado-workism: the new culture of work in Australia: since the late 1970s, Australia has witnessed the reinvigoration of a type of sadism in the workplace as decision-makers have restructured key socioeconomic and cultural institutions and practices.

There are important moments in history when people say ‘fuck work’ and assert their right to be lazy. The late twentieth [?] century French anarchists understood this well. They were combating the tyrannies of the new factory system and the deification by the church and state of labourers who toiled 15 hours a day for their masters. The growing parliamentary socialist movement also tried to gain respectability by creating an image of the working man as an upright, hardworking family man who obeyed the law and never beat his wife. In response, the anarchist Elisée Reclus proclaimed:

He who commands becomes depraved, he who obeys becomes smaller. Either way, as tyrant or slave, as an officer or as an underling, man is diminished. The morality which is born out of the present conception of the state and social hierarchy is necessarily corrupt. Religions have taught us that the fear of god is the beginning of wisdom, whereas history tells us that it is the beginning of all servitude and all depravity.

Shortly after, the French Socialist Albert Metin visited Australia to observe not anarchism but the new ‘working man’s paradise’. What has changed since Metin’s visit? Certainly not wage slavery. This remains the fate of most Australian employees. However, because of unemployment, today’s anally retentive employers are less likely to hear their workers tell them to ‘stick their job up their …’. Compared with before the 1980s, hours lost to strikes have also plummeted dramatically. For example, in 1994 there were 560 industrial disputes, the lowest number since 1940. A decade later, in 2003, there were 642 disputes; although this was 82 more than in 1994, this was still a very low number compared with the 2000 to 2800 industrial disputes each year between 1969 and 1976. It is not that more strikes are good in themselves; rather, they are a barometer of a whole range of aspects of industrial relations–from how organised workers are to the harmoniousness of workplaces to the general political climate (hostile or sympathetic towards striking). Australians’ working hours per week and hours of unpaid overtime are now among the highest in the OECD. Over a quarter of the workforce works more than fifty hours per week and 64 per cent of employees work either on weekends or at night. Also, according to the Job Futures/Saulwick Employee Sentiment Survey of 2002, 47 per cent of full-time employees work an average of 7.9 hours unpaid each week.

Much more, however, is at stake than mere numbers of hours worked. The workplace of paid employment is the last frontier. Significant numbers of households –though still a minority–have, in recent decades, undergone limited democratisation in terms of the sharing of tasks and decision making. In contrast, the sphere of paid work has gone backwards. It is the citadel of sadomasochism. While gender, race and other cultural signifiers remain important, paid work is perhaps the primary definer of social identity, social power, income and meaning. Everything else in Australian culture–children, art, community and love–is now secondary. For example, a recent report by Ruth Weston and colleagues on fathers, long working hours and family wellbeing found that only 33.2 per cent of the full-time employed fathers worked 35 to 40 hours (‘standard’ hours), while 21.8 per cent worked 41 to 48 hours, 23.6 per cent worked 49 to 59 hours, and 21.4 per cent worked 60 hours or more. Meek policy proposals for ‘family friendly’ workplaces are feeble substitutes for the radical questioning of the role and place of work that was common in earlier years, and is more desperately needed now.

For decades, radical socialists, anarchists and feminists were the principal critics of work in capitalist societies. After all, the sadistic heart of capitalism–money capital–cannot beat without labour power, both past and present. The labour of previous workers is stored in the machinery, buildings, commodities and infrastructure of capitalism which they helped make. Dead labour now dominates living labour as business people increasingly dispense with their workers and turn instead to the gifts of dead labour–technology. What Marx saw happening in the 19th century capitalist use of machinery was elementary compared with recent developments. A truly dramatic phenomenon is currently underway: whenever it is cost-effective and possible (in terms of production and customer relations), businesses are expelling living workers and replacing them with ‘dead labour’ (that is, new technology) or part-time labour. The great transition from labour-intensive workplaces to capital- or technology-intensive enterprises is only in its initial stages.

Marxists long imagined that a rise in unemployment would radicalise the proletariat. Instead, sadists have been reinvigorated and socialists and anarchists have been marginalised; they are now the zombies. The same has happened to many feminists. An earlier generation of feminists tried to create a world that did not replicate the dominant male practices and values operating in the marketplace. Unfortunately, many former male radicals and feminists have made career success their top priority, and actively embraced the very sadistic or dehumanised managerial work practices they once condemned.

Thus, the type of work one performs–whether it is paid work or unpaid domestic labour–continues to divide men and women, and pit women against each other. The bitter arguments waged by various ‘work-centred’ feminists against ‘maternal feminists’ are symptomatic of the triumph of the capitalist work ethic over earlier critiques of the profound alienation caused by modern workplaces. Former feminist iconoclasts, such as those in the Women’s Electoral Lobby (Eva Cox or Anne Summers, for example), are now mainstream advocates for abundant and good public child care so that mothers can toil away for their masters and mistresses–and become exactly like the model of respectable working men promoted by nineteenth-century French parliamentary socialists. Meanwhile, advocates of traditional gender roles who stress the importance of mothering in the early years of a baby’s life defend a vital dimension of human activity and form unlikely alliances with radicals who are protesting the all-consuming demands of market forces.

Whereas earlier radicals and reformers recognised the destructive and toxic nature of public and private sector workplaces, these insights have been largely shelved in the current conservative climate. Ambitious women, no less than their male counterparts, have trampled over others in their climb to the top. The idea of feminist values being able to replace or transform managerialist and shareholder interests remains a myth–or a dream.

Alienation from one’s community and the natural world, caused by the irrational market system and wage slavery, is even more pervasive today than it was thirty years ago. Fierce competition for scarce jobs in a deregulated labour market disciplines waverers. Government imposition of ‘mutual obligation’ stigmatises the ‘bludgers’ while the social pressure to work long hours to acquire ‘aspirational’ consumer assets increases. All of these have contributed to the successful reassertion of the ‘work ethic’. Not surprisingly, most Australians crave the financial and social power (as well as cultural status) provided by paid work; they feel empty, meaningless and socially inferior without it.

Old and New Forms of Sadism

Sadists have experienced fluctuating fortunes in the public sphere. The transition from feudal to capitalist societies in Europe involved the overthrow of absolutism in the public sphere and its enshrinement in the private sphere. The English Civil War of the mid-seventeenth century signalled the end of absolute monarchy with the execution of Charles I and the triumph of Cromwell’s parliamentary forces. The monarchy that was reinstated after Cromwell’s death was a constitutional monarchy, with its powers firmly circumscribed by the will of Parliament. This tradition remained in place until 1975, when the monarch’s representative, John Kerr, exercised an ‘absolutist’ or seemingly obsolete power and dismissed the Australian people’s elected representatives.

The dismissal of the Whitlam Government could be seen as a historical aberration. After all, many monarchs who claimed omnipotent powers over their subjects have been overthrown during the past three centuries. Hardly any remain on their thrones today. In parallel with the rejection of absolute monarchs, feudal societies had also witnessed changes at most other social levels. The formal bonds and stratified rules governing relations between lords, serfs and others were eventually dissolved in favour of legal statutes specifying universal citizenship rights in nation-states. The American War of Independence and the French Revolution of 1789 paved the way for this, as did numerous social struggles during the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, in the twenty-first century, the local sadists in Australia still bitterly resist human rights legislation–Australia is one of the last countries without a national bill of rights. Even the United Kingdom, for all its archaic monarchic powers and undemocratic structures (such as the House of Lords), is slowly joining the mainstream current of European human rights legislation.

If the principles of constitutional democracy–let alone republican democracy–remain fragile and poorly grounded in the Australian public sphere, the situation in the private spheres of family life and workplace is even worse: countless violations of democratic principles occur daily. The alarming scale of these abuses indicates that sadism is still riding high in the saddle, but the sadism practised in the contemporary Australian public sphere is qualitatively different from the old absolutism.

On the other hand, the sadism practised in the private sphere has direct continuity with earlier historical developments of market capitalism. This is because as constitutional and democratic rights were won from the seventeenth century onwards, informal bondage and serfdom retreated from the public sphere and consolidated their power in the factory and the home. Behind these private walls, a multitude of petty sadists exercised their absolute power over other subjects by treating them as objects. Workers were mere commodities, to be bought and dispensed with by the boss; wives and children were marital property, subject to the patriarch’s whims and desires.

Most twentieth century social and industrial struggles in Australia did not, perhaps surprisingly, seek revolutionary overthrow of either the owner or the institution of marriage. But neither did they manage to change much: efforts to impose ‘constitutional monarchy’, or social and legislative restraints, on bosses’ and patriarchs’ absolutism in the workplace and home remain as common now as they were a hundred years ago. Unfortunately, ‘democratic republics’ have not been widely established in the private business sphere, and a monarch still reigns supreme in most Australian workplaces and most homes.

The incidence of sadistic behaviour is so widespread in Australian workplaces that strangers could be forgiven for thinking that most employers and managers have never heard of the term ‘democracy’ and have no idea that employees are human beings in need of respect and open consultation. I am not just referring here to anti-bullying union websites such as the Bullies Down Under (which publicises acts of bullying), but also to other statutory bodies and victim support organisations that are flooded with explicit complaints of management bullying, harassment, intimidation, unfair dismissal and general abusive treatment. It would be fair to assume that these reports of workplace sadism, like reports of sexual assaults against women and children, are only the tip of the iceberg.

Despite mountains of PR material about ‘workers being the most precious resource’, a climate of fear and resentment pervades far too many Australian workplaces. A recent survey found that while 74 per cent of managers found staff morale a ‘core business concern’, two out of three executives had done nothing about it in the past twelve months. At the 2003 launch of the ACTU’s Workers’ Helpline, it was revealed that ‘over half the respondents (53 per cent) to union surveys report an unhappy and oppressive workplace, and 54 per cent say that intimidating behaviour like shouting, ordering and belittling people happens in their workplaces. Almost a third report abusive language’. Similarly, a 2003 report by Healthworks found that bullying, intimidation and abuse were so widespread in contemporary Australian workplaces that only 12 per cent of employees surveyed had not witnessed such behaviour.

In contrast to seventeenth and eighteenth century political debates about absolute monarchy, contemporary sadists do not invoke the ‘divine right of kings’ to justify their claims to unfettered power. Instead, sadism flourishes behind a veneer of ‘management-speak’ about productivity, competitiveness and freedom. It is not the demand of the king (as the embodiment of the state) to be free to rule without the constraint of the property owners in Parliament. Rather, today it is the demand of property owners and managers to ‘rule’ without interference by ‘the people’ or ‘the state’. Twenty years of government deregulation of private industries–it began in the early 1980s–have legitimised business notions of ‘freedom’ and control.

The practice of sadism depends on the nature of the workplace. In small companies, many employers respond to pressures from other businesses by resorting to sadism: that is, with irrational authoritarian responses that are highly counterproductive ‘solutions’ because they alienate employees. (As most small businesses are non-unionised, the threat to most small business owners, despite their anti-union rhetoric, actually comes from other businesses, especially large corporations.) In contrast, the workforce experience of sadism in large corporations is proportionate to two interrelated factors. First, there is an internal climate of insecurity that drives lower, middle and upper management towards sadistic practices (such as the bullying and abuse of employees by those in various lower or upper management positions); regular restructuring, takeover threats and downsizing only exacerbate this mixture of insecurity and sadism as managers try to save their own skins by driving their workers even harder. This internal climate of fear is driven by, or closely related to, continual external pressure to increase shareholder value at the expense of the company’s employees. Managers are pressured to deliver higher productivity and profits, which usually means cuts to workers’ conditions, disrespectful treatment of employees, and contempt or disregard for workers’ health and their family and social needs.

Public sector employees in a range of local, state and federal departments, and publicly funded employees in education, health and community services, find that their workplaces are increasingly prone to the same insecurity and ‘performance-driven’ pressures as are typical of the private sector. The difference is that the pressure to increase shareholder value is absent (except for employees in Telstra, and other such part-government/part-private enterprises). However, persistent public under-funding of services and political-administrative interference in the delivery of services are kinds of sadism that produce enormous work stress and humiliation, which in turn lead to other forms of workplace sadism.

Necessity and fear are the constant companions of sadism. Just as there can be no capitalism without workers, so there can be no sadistic culture without masochists. Of course most workers are not masochists by choice; they are so out of necessity, given the shortage of jobs. There is also a small number of individual investors who make money without employing workers. Many are under the illusion that their ‘detached’ investment or money-making is free of involvement in sadistic practices. However, ultimately, most forms of money-making in the market depend on the sum total of business activity and working conditions.

The degree of sadism practised in workplaces in various countries is closely related to the scarcity or abundance of labour and the presence or absence of democratic political institutions, especially free trade unions that will defend workers’ rights. For example, the Nazi and Soviet death camps and slave labour enterprises worked millions of prisoners until they died. ‘Enemies of the state’ in the Soviet Gulag, and non-Aryans such as Slavs in Hitler’s giant industrial war machine, were completely expendable. In ‘civilised capitalist’ societies like Australia, however, there is a smaller supply of human labour, because there is no political regime ready to deliver trainloads of subjects for large private corporations or state-owned industries, as was the case during the Third Reich or Stalin’s reign of terror. In Australia, there have long been many employers who admired Mussolini’s and Hitler’s industrial relations policies and who also crave the eradication of free trade unions. The desire to put profit before employees’ needs is visible in the rush by companies to offshore production in countries where workers have little or no protection. Fortunately, we still have parliamentary institutions to protect us from these potential fascists.

For over a hundred years, the most vicious type of sadism (leaving aside outright physical brutality, which is still common in some countries), and one that is still practised in workplaces, is piecework. Out of economic necessity, a culture of self-flagellation is institutionalised by sadistic employers. Anyone who has witnessed women with sewing machine needles stuck through their fingers, men who have cut off their fingers in abattoirs, or who is aware of the numerous deaths and injuries experienced by countless numbers of workers in other industries, will know what pain and sweat flows when people are not paid weekly wages but are paid according to the number of pieces made, slaughtered, packed or sold.

Piecework is the most degrading form of employment. Estimates by government bodies such as the Productivity Commission put the number of people classified as employees, but who are actually in some form of contract work or self-employment, at over 20 per cent of the total number of employees. Many of the new subcontractors and casual slaves for labour hire firms are former full-time workers downsized by public and private employers. Some may work from offices in their own nice homes instead of in dirty factories like traditional pieceworkers. A minority do well and enjoy their new ‘freedom’, but a substantial number of them earn less or little more than full-time regular employees do when their long six and seven-day weeks are taken into account. In contrast to traditional pieceworkers who hate their boss, the new self-employed pieceworkers have sometimes internalised the culture of masochism, suffering under the delusion that they are ‘the boss’. Sadists have little to fear from these new masochists.

Who’s in the Driver’s Seat?

In contrast to German and other European businesses that long ago instituted limited forms of industrial democracy, most Australian employers were very hostile to these types of reforms until the 1980s. What is striking about the new Australian workplace culture is how inhospitable it is to even moderate ideas of industrial democracy such as the European Works Councils Directive of the 1990s, which requires businesses to have workers represented at management level. This kind of limited form of industrial democracy has been shown to be quite compatible with the business practices of some of the most profitable corporations.

Many Left zombies have not come to terms with the new capitalism. They know that sadists thrive in workplaces that rely on casual workers or outsourced and subcontracted substitutes for full-time employees. Many Left workplace strategies–including the worthy goal of industrial democracy–are dependent on stability of employment, and on collective and consensual agreements. So in order to create what the Left would call a civilised workplace, current Australian employers would need to undo most of the major industrial relations changes of the past two decades. First, they would need to acknowledge that in the workplace, as everywhere else, they have a reciprocal relationship with human beings, not a short-term functional relationship to them as ‘human capital’–that is, as dispensable objects on individual contracts. Rather than doing this, though, major Australian employer groups and governments have watered down conditions and awards, promoted intimidating individual contracts, and done everything they can to weaken unions and collective representation in the workplace.

Given union invisibility in numerous workplaces (due to plummeting union membership and legal obstacles placed on unions entering workplaces), many employers have abandoned their earlier commitment to the workplace equivalent of ‘constitutional monarchy’. The struggle by the Howard Coalition Government to pass ‘unfair dismissal’ legislation, for example, is symptomatic of the demand by employers to return to a more feudal system, where they would have complete control over labour. It is sadistic legislation masquerading as a ‘job-creating measure’. According to employers’ lobbies, thousands of new jobs could be created [by] businesses able to get rid of ‘hopeless and unsackable workers’. In reality, if the legislation were passed, employees would be left with few rights, as anybody could be classified as ‘hopeless’ and sacked at the whim of the boss.

The list of sadists’ techniques–verbal abuse, speeding up the production line, and the ‘tyranny of intimacy’ (open-plan offices), for instance–has now been expanded to quasi-military, performance-enhancing, Outward Bound-type ‘bonding’ rituals (called ‘weekend retreats’, a name George Orwell would be proud of) are a new tool. These aim to increase employees’ productivity, self-reliance and teamwork. New technology also has highly contradictory implications. On the one hand, it undermines traditional worker-manager relations by vesting more initiative and control in the hands of individual employees. On the other hand, new technology is a wonderful bonus for sadistic employers. Electronic surveillance through cameras and computer and telephone monitoring keeps track of employees and their level of productivity. In call centres, for instance, the use of terms from the poultry farming industry tells us much about levels of sadism in different types of centres. Depending on whether it is called a ‘battery farm’, a ‘free range’ or a ‘barn-laid’ call centre, so there will be high or low staff turnover as workers have less or more freedom to vary their physical and voice movements and the duration of individual calls.

It is important to contrast the recent demands for greater rights for shareholders with the relative lack of concern shown by the media and Federal Government for the rights of employees. Numerous complaints have been made about the outrageous multi-million dollar packages earned by chief executives. Similarly, shareholders and customers have voiced their alarm about the lack of stringent regulatory enforcement of business codes in Australia, which seems to have almost directly led to fraud and a series of famous corporate collapses. Of course corporate lobbies such as the Business Council of Australia (BCA) are unhappy with demands for greater regulation. The old ‘divine right of kings’ is alive and well in many corporate boardrooms.

This is not to argue that all business leaders and employers are sadists. Even the BCA is divided: it has some members who are autocrats and others who are concerned about the widespread lack of ‘excellent workplaces’ where employees feel involved and respected. In fact a clear division has emerged within business circles in Australia and other countries about what management strategies are most likely to improve productivity and deliver higher profits. Note that this division over managerial philosophy is not driven by any concern for democratic principles. Rather, the concern is about the need to match global corporate benchmarks and not fall behind organisational innovation strategies adopted by business competitors.

Take for example, the application of Freud’s psychoanalytic theories of sadomasochism to organisations in order to differentiate between leaders and managers. Abraham Zaleznik, Professor of Leadership at the Harvard Business School and a clinical psychoanalyst, argues that:

managers, by their very nature, thrive on control, therefore anything that they perceive as costing them control is unsettling and is to be avoided … managers do not allow themselves the luxury of failure, whereas a leader will try, fail and try again, all the while learning new and valuable lessons. The manager, on the other hand, learns only one lesson in life–don’t fail–and to ensure non-failure, managers seldom take risks.

Thus, the continuing disputes between authoritarians and liberals over whether tough law and order measures or education and social reform are the best solutions to crime also reverberate in management practices in the business world. It is important to remember that those who stick to authoritarian models–as opposed to tolerant liberal models–are still mainly concerned to stop crime and achieve social order, not to redistribute wealth to ‘law-breakers’ and the poor. So, too, the contemporary managerial debates about ‘excellent workplaces’ are not about creating democratic workplaces for their own sake or, heaven forbid, furthering workers’ control. The term ‘democracy’ is rarely used in managerial debates. Better not to put dangerous ideas into the minds of workers! Happy, creative workplaces with new teamwork models and other fashionable organisational practices are more focused on improving market position, profit levels and shareholder returns than on creating humane, democratic workplace values per se.

Today, while there is widespread condemnation of child abuse and cruelty to animals, no such condemnation of work practices is heard: the workplace remains the last frontier where sadists outnumber more democratically minded employers. The contrast between a focus on ‘social responsibility’ and a focus on ‘capacity to manage’ is symptomatic of how much traditional industrial relations disputes have been overshadowed by new political concerns, or new consumer and environmental movements. The question is: what is to be done about companies that have good environmental records, produce safe consumer goods and are ‘good corporate citizens’, but still treat their employees in a sadistic manner? In a society oriented to consumers, it is all too common for the producers of goods and services–workers–to be devalued and overlooked. Conversely, those new innovative workplaces that are geared to creative output from individuals and teams stress their departure from the old industrial authoritarian model. The problem with some of these ‘new economy’, knowledge-based enterprises is that what they produce may be quite harmful to humans and the environment, or wasteful for society even though it is produced in ‘fun’ and stimulating workplaces.

Because the old struggle between labour and capital is culturally foreign–or perceived as irrelevant ancient history!–to a new generation of employees, many Australian workers who experience sadistic practices applied by their employers are not aware of the historical origins of those practices. Australia, like other OECD countries, has a variety of workplaces. Many in retail and other service areas employ one or two people, and hundreds of thousands of small businesses have fewer than ten employees. The conditions of employment in these small businesses range from good personal relations to suffocating and overbearing daily control. Establishing democratic rights in these small enterprises is quite different from doing the same thing in large impersonal enterprises that employ hundreds or thousands of workers.

But regardless of size, democratic workplaces and socially responsible enterprises are not likely to come via the adoption of managerial fashions. Without rights for workers, consumers and other stakeholders being enshrined in legislation, good workplaces and generous employers will continue to be in the minority. They will also have the same kind of status that charities have in social policy and the community services sector. There have always been caring Christians and others concerned to help the needy. But the glaring inability of charity to solve massive social inequality–in the absence of government services–is visible daily as millions of people walk past homeless people sleeping in the street. The affluent may be able to afford to give to charity, but a humanitarian and comprehensive welfare policy must be based on universal citizenship rights, not on charity. Equally, the many decent employers will not undermine or remove the army of sadists who continue to make life so unpleasant for workers that few would stay if they had a choice. But even new legislation, if it is not supported by a change of cultural attitude by employers and the employment of sufficient inspectors to enforce the laws, plus the development of anti-masochist views among employees, will ultimately prove ineffective. After all, there are plenty of laws that are currently ignored or subverted by employers due to lack of enforcement by state and federal governments.

Recently, the ALP and the ACTU have promoted the establishment of works councils. But as former Accord activist Max Ogden notes, these proposals are hardly comprehensive: they do not even cover occupational health and safety, or a systematic program to upgrade vocational skills, both of which are essential aspects of joint employee and management decision making. Ogden longs for the old Accord, the one that did much to undermine union activism despite promoting valuable gains such as occupational health and safety measures and a sense (among a minority of workers) that they could manage enterprises without the need for middle management. Yet he is correct to argue that works councils will hardly advance industrial democracy for all employees (unionised and non-unionised) in the current anti-union climate. As Ogden notes, ‘Until the union movement regains such fundamental democratic rights as proper recognition and the requirement that employers have to negotiate in good faith, issues such as works councils will not be seen as a high priority.’

Gaining lost rights for unions is an uphill battle. The power of sadism extends well beyond the workplace, but making the links between the unacceptability of absolutism in the public sphere and its dominance in the private sphere is easier said than done. This is partly because the logic of destructiveness that permeates Australian society is nourishing a new form of authoritarianism that is quite different from earlier forms of absolutism. This form of sadism thrives upon a new definition of citizenship rather than on the old ‘born to rule’ concept that denied citizenship rights to various groups of people. What is so powerful about the new form of control is that in many instances it does not rest on the old combination of coercion and consent that Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci and other radicals pointed to when discussing the domination of capitalists. Sadism also thrives where there is a combination of cultural masochism and indifference to the exercise of democratic power.

~ Zombies, Lilliputians and Sadists: The Power of the Living Dead and the Future of Australia by Boris Frankel (Curtin University Books, September 2004).

Pingback: Some notes on anarchism + anti-fascism | slackbastard