[now]

::::::: Ask Jarrod :::::::

@ndy : What will be the effects of the sedition laws on writers? And is it true that Frank Moorhouse was once a member of a militant anarchist group?

“On the face of it, there’s a pretty straightforward effect of sedition laws upon writers: they get jailed. However, in this session [at the Byron Bay Writers Festival], we are to find out that in 21st century Australia it means officers of the law bearing court warrants and specially designed hammers will come around to your publisher’s office and smash the computer hard drives containing your manuscript. In Indonesia, it may mean you may lose your house – and possibly ‘disappear’ when your words are considered to have called for the overthrow of the prevailing government – or indeed, upset those in power…

Frank Moorhouse comes to the microphone and details his experience of freedom of expression and its repression during the 1950s – noting that while members of the Communist Party and their ‘fellow travellers’ were hunted, spied upon and harangued, his own efforts in a militant [er] anarchist group were considered no threat to the nation, according to his own ASIO file.”

Australian Law Reform Commission Inquiry on Sedition

[then]

::::::: Ask Bishop Wenski :::::::

@ndy : Bishop Wenski, who are the anarchists, and what do they want?

“At the beginning of the 20th century, the world found itself in a war started when the Austrian prince was shot in Sarajevo by someone then called an “anarchist.” Today we would call him a terrorist. Then too, the world was undergoing an accelerated process of globalization, thanks to the steamship, the telegraph and the industrial revolution. Many of the anarchists of the day were anti-globalists, so then as now terrorism is, in a sense, a reaction to globalization.”

::::::: Ask Doctor Bob :::::::

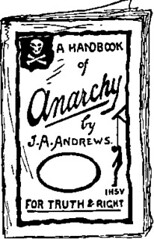

@ndy : “It may be as well to point out here that the dynamite policy has nothing to do with Anarchy” said J.A. Andrews in 1894. What did the authorities of Victoria think, and how did they react to the publication of Andrews’ Handbook of Anarchy?

“A letter from the Chief Secretary and Premier, Dibbs, 14 June 1894 to the Hon. C.G.Heydon, (Solicitor-General?) with a copy of the pamphlet, Handbook of Anarchy attached, asked for his careful perusal ‘with a view of considering whether any action should be taken regarding it’. In the context of the time, Dibbs doubtless had some charge like ‘sedition’ or ‘incitement to ‘murder’ in mind. After some deliberations, Andrews was prosecuted and convicted for selling this ‘pamphlet’ without legal imprint, even though many other publications including the Hansard of the NSW Parliament, were seriously in breach of the rule. Andrews had his name and address on the publication, but not in the ‘correct’ place. The Bulletin received only a polite letter of censure for a similar, technical breach…

When the authorities came to peruse The Handbook of Anarchy, which should be considered Andrews’ definitive statement, they found nothing they could hang serious charges on. So, through the person of Whittingdale Johnson, who had already sentenced Broken Hill strike leaders to jail in 1892, they settle for perjury of themselves and for a minor curtailment of Andrews’ activities and of that of two comrades, who were arrested for distributing the pamphlet. No court record remains of this ‘trial’ because no ‘trial’ actually occurred. No witnesses were called, no evidence taken. The judge, bouncing up and down, shouting, ‘But you must not publish sedition! You must not publish sedition!’, handed down penalties which bore no relation to a charge of sedition, and no relation to reality. He simply refused to listen to Andrews’ defence. (See Bulletin, 3 November, 1894, p3.)

The authorities were able to gain the anti-anarchist publicity that would ensure public acceptance of the judge’s arbitrary behaviour if they ever heard of it, not from this case — since they were on such particularly shaky ground — but from a set of fortuitous circumstances which largely depended for their effect on previous anti-anarchist hysteria. In France, just days before the Sydney ‘trial’, [Sante Jeronimo Caserio] assassinated President Carnot. On 30 June, a scandal-sheet called the Bird O’Freedom center-paged a scurrilous, vicious attack on anarchism, Andrews and a so-called anarchist farm at Smithfield. Using the French murder as the jumping-off point, the article correlated social revolution with seas of blood, and with men forcing women to share their sexual favours around. Marx and Engels were said to have been the leaders of the Paris Commune, and anarchists, unionists, Satan and mad fanatics were all, literally, lumped together.”