- Or, You don’t need a a dialectical-materialist philosopher and psychoanalyst, To know which way the wind blows.

Or, What you mean ‘we’, paleface?

Resistance Is Surrender

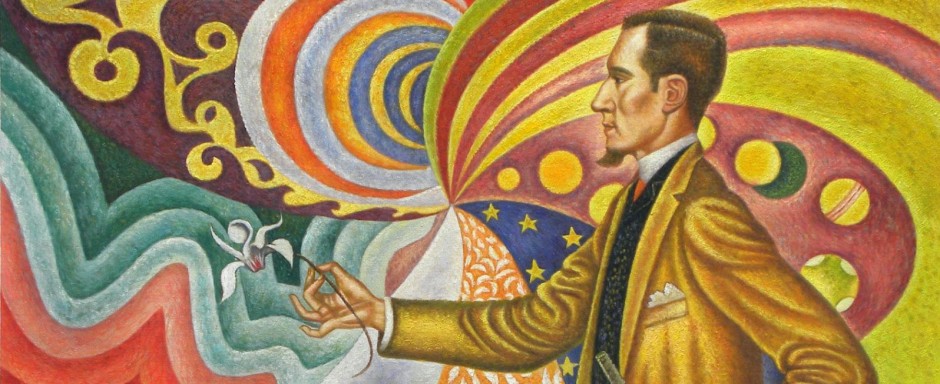

Slavoj Žižek

London Review of Books

November 15, 2007

One of the clearest lessons of the last few decades is that capitalism is indestructible. Marx compared it to a vampire, and one of the salient points of comparison now appears to be that vampires always rise up again after being stabbed to death. Even Mao’s attempt, in the Cultural Revolution, to wipe out the traces of capitalism, ended up in its triumphant return.

Today’s Left reacts in a wide variety of ways to the hegemony of global capitalism and its political supplement, liberal democracy. It might, for example, accept the hegemony, but continue to fight for reform within its rules (this is Third Way social democracy).

Or, it accepts that the hegemony is here to stay, but should nonetheless be resisted from its ‘interstices’.

Or, it accepts the futility of all struggle, since the hegemony is so all-encompassing that nothing can really be done except wait for an outburst of ‘divine violence’ – a revolutionary version of Heidegger’s ‘only God can save us.’

Or, it recognises the temporary futility of the struggle. In today’s triumph of global capitalism, the argument goes, true resistance is not possible, so all we can do till the revolutionary spirit of the global working class is renewed is defend what remains of the welfare state, confronting those in power with demands we know they cannot fulfil, and otherwise withdraw into cultural studies, where one can quietly pursue the work of criticism.

Or, it emphasises the fact that the problem is a more fundamental one, that global capitalism is ultimately an effect of the underlying principles of technology or ‘instrumental reason’.

Or, it posits that one can undermine global capitalism and state power, not by directly attacking them, but by refocusing the field of struggle on everyday practices, where one can ‘build a new world’; in this way, the foundations of the power of capital and the state will be gradually undermined, and, at some point, the state will collapse (the exemplar of this approach is the Zapatista movement).

Or, it takes the ‘postmodern’ route, shifting the accent from anti-capitalist struggle to the multiple forms of politico-ideological struggle for hegemony, emphasising the importance of discursive re-articulation.

Or, it wagers that one can repeat at the postmodern level the classical Marxist gesture of enacting the ‘determinate negation’ of capitalism: with today’s rise of ‘cognitive work’, the contradiction between social production and capitalist relations has become starker than ever, rendering possible for the first time ‘absolute democracy’ (this would be Hardt and Negri’s position).

These positions are not presented as a way of avoiding some ‘true’ radical Left politics – what they are trying to get around is, indeed, the lack of such a position. This defeat of the Left is not the whole story of the last thirty years, however. There is another, no less surprising, lesson to be learned from the Chinese Communists’ presiding over arguably the most explosive development of capitalism in history, and from the growth of West European Third Way social democracy. It is, in short: we can do it better. In the UK, the Thatcher revolution was, at the time, chaotic and impulsive, marked by unpredictable contingencies. It was Tony Blair who was able to institutionalise it, or, in Hegel’s terms, to raise (what first appeared as) a contingency, a historical accident, into a necessity. Thatcher wasn’t a Thatcherite, she was merely herself; it was Blair (more than Major) who truly gave form to Thatcherism.

The response of some critics on the postmodern Left to this predicament is to call for a new politics of resistance. Those who still insist on fighting state power, let alone seizing it, are accused of remaining stuck within the ‘old paradigm’: the task today, their critics say, is to resist state power by withdrawing from its terrain and creating new spaces outside its control. This is, of course, the obverse of accepting the triumph of capitalism. The politics of resistance is nothing but the moralising supplement to a Third Way Left.

Simon Critchley’s recent book, Infinitely Demanding, is an almost perfect embodiment of this position.[*] For Critchley, the liberal-democratic state is here to stay. Attempts to abolish the state failed miserably; consequently, the new politics has to be located at a distance from it: anti-war movements, ecological organisations, groups protesting against racist or sexist abuses, and other forms of local self-organisation. It must be a politics of resistance to the state, of bombarding the state with impossible demands, of denouncing the limitations of state mechanisms. The main argument for conducting the politics of resistance at a distance from the state hinges on the ethical dimension of the ‘infinitely demanding’ call for justice: no state can heed this call, since its ultimate goal is the ‘real-political’ one of ensuring its own reproduction (its economic growth, public safety, etc). ‘Of course,’ Critchley writes,

- history is habitually written by the people with the guns and sticks and one cannot expect to defeat them with mocking satire and feather dusters. Yet, as the history of ultra-leftist active nihilism eloquently shows, one is lost the moment one picks up the guns and sticks. Anarchic political resistance should not seek to mimic and mirror the archic violent sovereignty it opposes.

So what should, say, the US Democrats do? Stop competing for state power and withdraw to the interstices of the state, leaving state power to the Republicans and start a campaign of anarchic resistance to it? And what would Critchley do if he were facing an adversary like Hitler? Surely in such a case one should ‘mimic and mirror the archic violent sovereignty’ one opposes? Shouldn’t the Left draw a distinction between the circumstances in which one would resort to violence in confronting the state, and those in which all one can and should do is use ‘mocking satire and feather dusters’? The ambiguity of Critchley’s position resides in a strange non sequitur: if the state is here to stay, if it is impossible to abolish it (or capitalism), why retreat from it? Why not act with(in) the state? Why not accept the basic premise of the Third Way? Why limit oneself to a politics which, as Critchley puts it, ‘calls the state into question and calls the established order to account, not in order to do away with the state, desirable though that might well be in some utopian sense, but in order to better it or attenuate its malicious effect’?

These words simply demonstrate that today’s liberal-democratic state and the dream of an ‘infinitely demanding’ anarchic politics exist in a relationship of mutual parasitism: anarchic agents do the ethical thinking, and the state does the work of running and regulating society. Critchley’s anarchic ethico-political agent acts like a superego, comfortably bombarding the state with demands; and the more the state tries to satisfy these demands, the more guilty it is seen to be. In compliance with this logic, the anarchic agents focus their protest not on open dictatorships, but on the hypocrisy of liberal democracies, who are accused of betraying their own professed principles.

The big demonstrations in London and Washington against the US attack on Iraq a few years ago offer an exemplary case of this strange symbiotic relationship between power and resistance. Their paradoxical outcome was that both sides were satisfied. The protesters saved their beautiful souls: they made it clear that they don’t agree with the government’s policy on Iraq. Those in power calmly accepted it, even profited from it: not only did the protests in no way prevent the already-made decision to attack Iraq; they also served to legitimise it. Thus George Bush’s reaction to mass demonstrations protesting his visit to London, in effect: ‘You see, this is what we are fighting for, so that what people are doing here – protesting against their government policy – will be possible also in Iraq!’

It is striking that the course on which Hugo Chávez has embarked since 2006 is the exact opposite of the one chosen by the postmodern Left: far from resisting state power, he grabbed it (first by an attempted coup, then democratically), ruthlessly using the Venezuelan state apparatuses to promote his goals. Furthermore, he is militarising the barrios, and organising the training of armed units there. And, the ultimate scare: now that he is feeling the economic effects of capital’s ‘resistance’ to his rule (temporary shortages of some goods in the state-subsidised supermarkets), he has announced plans to consolidate the 24 parties that support him into a single party. Even some of his allies are sceptical about this move: will it come at the expense of the popular movements that have given the Venezuelan revolution its élan? However, this choice, though risky, should be fully endorsed: the task is to make the new party function not as a typical state socialist (or Peronist) party, but as a vehicle for the mobilisation of new forms of politics (like the grass roots slum committees). What should we say to someone like Chávez? ‘No, do not grab state power, just withdraw, leave the state and the current situation in place’? Chávez is often dismissed as a clown – but wouldn’t such a withdrawal just reduce him to a version of Subcomandante Marcos, whom many Mexican leftists now refer to as ‘Subcomediante Marcos’? Today, it is the great capitalists – Bill Gates, corporate polluters, fox hunters – who ‘resist’ the state.

The lesson here is that the truly subversive thing is not to insist on ‘infinite’ demands we know those in power cannot fulfil. Since they know that we know it, such an ‘infinitely demanding’ attitude presents no problem for those in power: ‘So wonderful that, with your critical demands, you remind us what kind of world we would all like to live in. Unfortunately, we live in the real world, where we have to make do with what is possible.’ The thing to do is, on the contrary, to bombard those in power with strategically well-selected, precise, finite demands, which can’t be met with the same excuse.

See also : Lettuce to the Cabbage : TJ Clark: Chris Harman: André Bénichou (December 13, 2007) | David Graeber (January 3, 2008) | Slavoj Žižek (January 24, 2008) | Simon Critchley’s review of Violence by Slavoj Žižek

REFERENDUM ON ZIZEK?

David Graeber

Slavoj Žižek is a delightful provocateur and an extraordinarily gifted intellectual comedian. One day he’s denouncing do-gooder capitalists like George Soros by insisting capitalism is an irredeemable system of structural violence; a few weeks later, he’s informing the Left there’s no chance of ever overcoming capitalism, but they should take hope in the fact that “we can do it better”. One day he’s embracing Lenin as a man whose aim was to destroy all states forever, the next he’s arguing the state must be maintained as the only possible remaining bulwark against capitalism. To respond to such statements as if they educed a consistent political position seems slightly oafish. Still, if you choose someone like this as a book reviewer, your readers are unlikely to learn much about the book. Worse, “Resistance is Surrender,” which purports to be a review of Simon Critchley’s Infinitely Demanding, is clearly intended less as a review than as a political intervention aimed to head off any possibility that LRB’s readers might give serious consideration to its message.

That would be unfortunate.

Critchley’s book is important, it seems to me, because it is a kind of overture. It is almost unheard of for professional intellectuals—philosophers, no less—to engage seriously with radical social movements. The reason is simple enough: it requires listening. The last decade has seen a profound change in world politics, as social movements from Argentina to Japan increasingly reject the very idea of seizing state power, of creating freedom at the point of a gun, and began instead concentrating on the reinvention of new forms of democracy, sociality, and exchange. The intellectual classes have never known quite what [to] make of it. Most reacted with condescension when the global justice movement first appeared on the horizon around 2000; some soon switched to giddy enthusiasm, followed by a sense of hurt dismay on discovering the movement wasn’t looking for a vanguard. Over the last few years, as it has become apparent that revolutionary transformation of the sort the movement aims to achieve is going to take a great deal of time and patience, former intellectual allies have begun tumbling over each other to abandon ship, and find some “progressive capitalists” to whom to sell their souls (though so far, without a great deal of success).

Critchley is one of the few who has made a serious effort to listen, to entertain the possibility, in effect, that those who are actively engaged in fighting capitalism and its empires might themselves have something relevant to say, to try to understand what they are trying to achieve, and how the intellectual tools at his disposal might be helpful. The book does not simply propound a Levinasian ethics, understood as an infinite responsibility towards otherness, it is in itself an attempt to practice it. Žižek appears to object to this project on principle (rather oddly, considering he endorses the book in precisely these terms on his blurb on the back cover). When you shave away the posturing, his real message to LRB’s reviewers is simple: you are intellectuals. Intellectuals have always been, and always must be, whores to power in some form or another. Obviously, Žižek can’t quite out and say this: so he conveys it in the form of a series of rather dishonest rhetorical maneuvers, mostly revolving around deployment of the term “we”. “We” are intellectuals, “we” are the Left (since the Left apparently consists primarily of intellectuals), but we also seem to include anyone from Tony Blair and the Democratic Party to the current rulers of the People’s Republic of China. As a result “we” obviously cannot stand opposed on principle to cruise missiles and interrogation chambers because our real brothers and sisters are not those being blown up by or strung up in them, but rather, those pushing the buttons and calculating stress positions.

Well, of course we can make that choice if we like. For most of human history, those who made their livings by writing mostly have. Still, I’d offer two points readers might wish to consider:

First, capitalism will not really be around forever. An engine of infinite expansion and accumulation cannot, by definition, continue forever in a finite world. Now that India and China are buying in as full players, it seems reasonable to assume that within at most 50 years, the system will hit its physical limits. Whatever we end up with at that point, it will not be a system of infinite expansion. Therefore it will not be capitalism. It will be something else. However, there is no guarantee that this something will be better. It might be considerably worse. Might we not do well to at least consider what something better might be like? If nothing else it seems an odd moment to call off all speculation about alternatives. And if one does wish to think about alternatives to capitalism, how better to do this than to engage with those building such alternatives in the present?

Second, to be able to do this, we will probably have to learn to get over ourselves a little. This is the eventuality against which Žižek seems to be making his heroic stand. After all, why choose Chavez? Why not, say, Evo Morales, who unlike Chavez really was placed in power by, and remains answerable to, genuine social movements? Obviously: for that very reason. Could we really imagine someone like Žižek, even in his fantasies, patiently listening to the demands of the directly democratic assemblies of El Alto? Chavez, on the other hand, is precisely the political figure such an intellectual would wish himself to be: a virtuoso performer and political comedian holding power with no real responsibilities to anyone except the pleasure of his audience. Sure, it’s a seductive fantasy. But it’s precisely the fantasy we have to get past if we want to make a genuine difference in the world.

Check it out now! A funk soul rebel: BOOKSURFER : Books & Internet Resources | Scott McLemee, Zizek Watch, The Chronicle of Higher Education, February-July 2004

- Žižek

“Yes, he’s married. His wife, the filmmaker and writer Astra Taylor, did a documentary about Slavoj Žižek. How cool is that?” (Ten Years Of In The Aeroplane Over The Sea, stereogum.com, February 8, 2008)

“Since the deaths of Jacques Derrida in 2004 and Jean Baudrillard in 2007, the Slovenian critic Slavoj Žižek has quickly cemented his position as the world’s most prominent philosopher and cultural theorist.” (Heart of darkness, Matthew Taunton, New Statesman, January 31, 2008)

“Žižek leaves no social or cultural phenomenon untheorized, and is master of the counterintuitive observation.” New Yorker

“Unafraid of confrontation and with a near-limitless grasp of pop symbolism.” The Times

“Žižek is one of the few living writers to combine theoretical rigor with compulsive readability.” Publishers Weekly

“I prefer to think of myself as some[one] who, so as not to offend others, pretends that he is human. In fact, I am a monster.” Žižek

wow – you are posting my original letter, not the one that was published, with all the broader points criticizing intellectuals cut out! where did you get that?

David

hey david,

it came to me in a dream. by which i mean, the anarchist academics list.

cheers,

andy.

compare! contrast!

Zizek has positioned himself as an intellectual celebrity and court jester, but in recent times, he’s copped plenty of flak on different positions. Much of his work is repetitive, and filled with recycled material. He seldom develops a coherent argument – one can read a Zizek paper, find plenty of amusing and provocative quotes, but still fail to find much in the way of a sustained thesis. His recent ‘Christian turn’ is something that I also find rather unconvincing.

On the other hand, I’m pleased to see Lacanian theory in the public eye. Zizek does as good a job as anybody of popularising it, and furnishing some rather difficult concepts with amusing examples. Naturally, this stuff is probably not of major interest to activists.

Politically, there are many problems with Zizek’s work, but I still think he’s worth a read, if only as a counterpoint to the bone-dry, theory-free leftism of the Anglosphere generally (and someone like Chomsky, specifically). As a theorist of ideology, I think he is relatively successful, and this for me makes up for some of his less entertaining antics.

If Zizek has found God, it must have been by way of his Son, Lenin — I thought it was Terry Eagleton what’s gone all gooey-eyed over Xtianity. Oh yeah, Chomsky.

Chomsky has a point about the Parisiennes, to some extent, but I think he overplays his hand. This point comes through in his linguistic work also. He admires mathematics and physics (not illegitimately, perhaps) as the ideal sciences, but then also avers that social sciences ought to proceed along the same lines. Consequently, almost a whole century’s worth of continental philosophy is alien to him.

He did have a minor rapprochement with Foucault, however, and you can find their discussion on YouTube somewhere.

Here’s a Zizekian link on the subject of Chomsky:

http://bad.eserver.org/issues/2002/59/zizek.html

Chomsky & Foucault on Human Nature: Justice Vs. Power (Hilversum: NOS-television, November, 1971)

Transcript : http://www.chomsky.info/debates/1971xxxx.htm

As the least intellectual of comment makers I feel I get a free pass to say that Zizek is a turd and always seemed to me to have his head up his own backside.

As I noted elsewhere…

Zizek coquettes with Lenin, and critiques some of the more easy and comfortable liberal truisms, but for all that, my feeling is that he is yet to shake off much of his bourgeois liberal hypocrisy.

I do think his critique of ideology has some value in that it marries some Marxist concepts with Lacanian stuff. The sublime object of ideology is an early work of his that is pretty good in this regard.

I wouldn’t read too much into Z’s criticisms of anarchism. Of the Z material I’ve read, I can’t recall any critique of the subject that lasted more than a line or two. On another blog recently, some were arguing (in the context of Balkan troubles) that Z was/is some kind of apologist for Slovenian nationalism. Whether this is true, I think there are limits to which Z can be taken politically seriously.

The ‘universal dimension’ is one of Z’s more interesting angles, though in part I suspect he’s lifted bits of it from Badiou (along with the Pauline Christian turn).

I don’t know anybody who regards Z as a ‘superstar’, though there is a journal of Zizek studies, which is mildly unbelievable:

http://zizekstudies.org/index.php/ijzs/issue/archive

He’s a one man publishing phenomenon, who happens to have a penchant for Latin American lingerie models more than a ‘superstar’. Academics and intellectuals often react unkindly to perceived fads, so any purported star status may not work in his favour.

Come on, vogue

Let your body move to the music (move to the music)

Hey, hey, hey

Come on, vogue

Let your body go with the flow (go with the flow)

You know you can do it

All you need is your own imagination

So use it that’s what it’s for (that’s what it’s for)

Go inside, for your finest inspiration

Your dreams will open the door (open up the door)

It makes no difference if you’re black or white

If you’re a boy or a girl

If the music’s pumping it will give you new life

You’re a superstar, yes, that’s what you are, you know it…

Charlie Bertsch, from the Introduction to Doug Henwood’s interview with Z:

As for Z’s reaction to this, I think he utilises it as another weapon in his armoury. And in a way, good luck to him: keeps him up to his neck in lingerie models anyway, and allows him to maintain a reasonably healthy bank balance. Inre his views on anarchism, yeah, they’re facile, but then so are the views of others in the same constellation, including Badiou.

Hi all,

I am pretty obsessed with Zizek at the moment, and have an essay on the above quoted piece in the works (don’t hold your breath, it will take me a month to finish my thesis then a month running around in circles then I’ll finish it). Yes he is both brilliant and full of bullshit but his basic ideas for radical politics are interesting:

1) that there is no clear revolutionary subject – rather a subject can only emerge from an engagement with the difficult problematic “real” — the grubby indivisible remainder;

2) that we need to practice utopia by first withdrawing from the political co-ordinates of society, and then acting in ways that actually challenge the co-ordinates;

3) that it is not enough to just try to refuse capital, we have to make other social realities;

4) this involves getting your hands dirty (Terror) and avoiding moral binaries;

5) not really interested in the Leninist party but rather the Leninist act of acting “out of time” – not waiting for the objective conditions to ripen.

Sure it’s not perfect but I think any really [productive?] discussion on Zizek should focus on the substance of his work. The Zizek is a turd argument is just as facile as the Zizek is wonderful one. Both are the standard ways we talk about celebrities.

I was thinking as I was walking home from the pub that the more Zizek starts to write explicitly on politics the less popular he will be – but perhaps his work might be more influential.

rebel love,

Dave

PS. And yeah his work on ideology is also really interesting.

and so far the Critchley book is a bit arse

Hi All,

One of the things that is really annoying about this Zizek piece is that I don’t think it is actually about what it says it is about. Take for example the attack on the Zapatistas. To my mind, in some ways, the Zapatistas are very similar to the politics of practising utopia that Zizek champions. In some ways they even conform to his Lacanian version of the subject – the way that the previous identities of some of the EZLN are ‘dead’, their wearing of masks, the whole idea of being silent so they can speak and so on.

I suspect that the real targets are Negri and autonomists and by attacking Critchley, Badiou. Critchley’s book is very sympathetic to Badiou and his suggestions for politics are very similar. After being a populariser of Badiou in previous works, Zizek is now turning on him (Cf. The Parallax View) – particularly Badiou’s suggestions for localised site specific non-state politics. Yes there are still some similarities and it would take a very careful reading to really prize them out.

communist dreams

Dave