The National Gallery of Victoria is curently showing an exhibition of works by Camille Pissarro, The First Impressionist. And ironically, while contemporary local anarchists will be celebrating ten years of the Black Star on March 4th, Melbourne’s yuppies will be celebrating the opening of the exhibition at a “Parisian soiree”. Join them, if you wish, “for a beautiful French inspired evening with live entertainment, wine, canapés and a preview of the exhibition.” Admission is available to anyone with $55.00 to spare, but be quick; bookings close 5pm this Thursday, March 2nd. (Unfortunately, no discounts are available to rebels, although friends have assured me that sneaking in isn’t out of the question…)

The National Gallery of Victoria is curently showing an exhibition of works by Camille Pissarro, The First Impressionist. And ironically, while contemporary local anarchists will be celebrating ten years of the Black Star on March 4th, Melbourne’s yuppies will be celebrating the opening of the exhibition at a “Parisian soiree”. Join them, if you wish, “for a beautiful French inspired evening with live entertainment, wine, canapés and a preview of the exhibition.” Admission is available to anyone with $55.00 to spare, but be quick; bookings close 5pm this Thursday, March 2nd. (Unfortunately, no discounts are available to rebels, although friends have assured me that sneaking in isn’t out of the question…)

Rebellion As Titillation

The dreamer whose dreams are non-utilitarian has no place in this world. Whatever does not lend itself to being bought and sold, whether in the realm of things, ideas, principles, dreams or hopes, is debarred. In this world the poet is anthema, the thinker a fool, the artist an escapist, the woman of vision a criminal.

— Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945)

‘Once a rebel, always a rebel’, says NGV curator Ted Gott of Camille Pissarro, the first Impressionist, on the eve of a major touring exhibition, writes Robin Usher.

I’m the first to admit that the art and science of daubing paint onto canvas isn’t exactly one of my areas of expertise. (On the other hand, what is?) Still, I’m curious to know what kind of an impression Pissarro, anarchist and Impressionist, is capable of making today, 103 years after his death. According to Usher:

Camille Pissarro is revered today as a father of Impressionism. But the radical spirit of one of the world’s most revolutionary art movements stayed with him all his life, much to the horror of his dealer.

“He was an active supporter of anarchist politics well into middle age, at a time when anarchists were bombing restaurants, theatres and horse-drawn taxis,” says the National Gallery of Victoria’s senior curator of international art, Ted Gott.

“It would be the equivalent of a contemporary Melbourne artist supporting al-Qaeda. They were dangerous times and he went out on a limb for his beliefs,” he says.

“Sales of his work dropped off because people stopped buying his paintings.”

So according to Ted, not only was Pissarro “the equivalent of a contemporary Melbourne artist supporting al-Qaeda”, he was also an anarchist rebel prepared to sacrifice market share for political principle!

Nah, I don’t believe it either.

Seriously though, Gott’s facile equation ‘fin de siècle anarchism = twenty-first century Al Qaeda’ is so routine — indeed, systematic — as to be almost unremarkable.

Almost.

In the current political climate, it’s damaging. As I write, the artist Stephen Kurtz is being persecuted by US authorities under the rubric of ‘fighting terrorism’, and is facing 20 years imprisonment as a result. In reality, Kurtz is being punished for his (and CAE’s) success at using art to draw attention to the damaging effects of corporate and state power, especially in the field of biotechnology. And opposition — even ‘artistic’ opposition — to corporate control over biology is sufficient reason for the FBI to place Kurtz in the same category as Al Qaeda, it seems.

Anarchism As Terrorism

“I would rather kill chickens than kill kings. Chickens are good to eat. But a king, of what use is he?” — Errico Malatesta

The years 1892 to 1901 are sometimes referred to as The Decade of Regicide: those who kicked their gold-plated buckets at this time included President Sadi Carnot of France in 1894, Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas of Spain in 1897, the Empress Elizabeth of Austria in 1898, King Humbert of Italy in 1900, and President William McKinley of the United States in 1901.

The anarchist who bombed a theatre has a name and it’s Santiago Salvador Franch. He was executed in 1894. He threw two bombs (on November 7, 1891 — or 1893, sources vary) into the audience at The Grand Theatre of the Liceu during a performance of the opera William Tell, killing 22 (or possibly as many as 30) people. The anarchist who bombed a restaurant has a name and it’s Emile Henry. On February 12, 1894, Henry detonated a bomb at the Café Terminus in the Parisian Gare Saint-Lazare killing one person and wounding twenty.

As for anarchists bombing horse-drawn taxis… who knows? I suspect Gott may be referring to an event that took place on September 16, 1920, when a “TNT bomb planted in [an] unattended horse-drawn wagon exploded on Wall Street opposite House of Morgan, killing 35 persons and injuring hundreds more. Bolshevist or anarchist terrorists [were] believed responsible, but [the] crime [was] never solved.” If Ted has evidence regarding anarchist involvement, I’m sure US authorities — or, more likely, historians — would be keen to hear from him.

Dunno, but perhaps Gott should read Richard Bach Jensen’s ‘Daggers, Rifles and Dynamite : Anarchist Terrorism In Nineteeth Century Europe’ (Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol.16, No.1, Spring 2004, pp.116-153) for enlightenment. In summary, Jensen writes:

While the number of assassinated heads of state and government, and of monarchs of major countries was unprecedented, the anarchists, outside of Spain, killed relatively few people. Nonetheless, the anarchists’ desire for dramatic signs of vindication, the authorities’ and the public’s fears of a vast anarchist conspiracy and the media’s hunger for sensational news combined to create the mirage of a powerful terrorist movement sweeping through nations and across the world.

In fact, according to Jensen’s calculations, in 1890s France, Spain and Italy — the three countries in which the majority of dastardly anarchist outrages such as these took place — “real or alleged anarchists killed more than sixty and injured over 200 people with bombs, pistols and daggers”. Further, while “No one has yet attempted to calculate the total number of European and world victims of anarchist terrorism… [f]or the period 1880-1914 (excluding Russia) about 150 people died and over 470 were injured as a result of real or alleged anarchist attacks”.

By way of comparison, one might consider the many casualties that wars produced during the period 1880-1914. For example, four times as many Australians (606) died helping to keep South Africa British in the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902 than anarchists allegedly killed during this entire period; casualties in the Herero War in German Southwest Africa (1904-07) totalled 75,000; while Mike Davis (Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (2001)) argues that the business policies of the imperial European landlords, merchants and bureacrats in the face of the El Niño drought intensified these famines and thereby caused millions of deaths during the period 1876-1900.

Still, the millions (upon millions) of victims of European capitalism and imperialism weren’t Presidents or Prime Ministers, Kings or Queens, so who cares? In fact, I expect that contemplating their fate — and the reasons why Pissarro dedicated much of his life and work to overthrowing the social structures responsible for their deaths — would only spoil, say, “a beautiful French inspired evening with live entertainment, wine, canapés and a preview of the exhibition”. And let’s face it, which is more important?

Art As Commerce

Of course, Pissaro’s politics is not the only remarkable fact about Pissarro, Impressionism, or, importantly, their legacy to the local Victorian economy:

Of course, Pissaro’s politics is not the only remarkable fact about Pissarro, Impressionism, or, importantly, their legacy to the local Victorian economy:

[The Pissarro exhibition] follows the NGV’s 2004 Impressionism exhibition that generated $25.7 million for the Victorian economy and attracted more than 380,000 visitors, including 78,000 from interstate and overseas…

An outcome that would, no doubt, generate joy in Pissarro’s heart were he alive today. (Then again, probably only if he could use it to subsidise local anarchist projects.) Still, there’s more to be made of Pissarro’s body than money. His ideas, too, may be recuperated, as Usher and Gott explain:

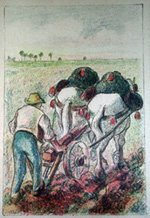

But Pissarro’s radicalism is [also] apparent in the subjects he painted in what became early impressionist works. Unlike Monet, who chose attractive subjects, he painted mundane stretches of rural life where nothing seems to be going on.

“He might choose a slice of muddy road, a field of cabbages or a patch of sky. But he was able to make these uninteresting subjects into extraordinary art,” Gott says…

Pissarro remained true to his [anarchist] politics even when his work became popular towards the end of his life. Because of an eye condition, he could no longer paint out of doors and began to paint cityscapes seen through hotel windows. Even in these, the individuality of the people of the street is apparent.

“His empathy with the people can be discerned right to the very end,” Gott says.

While today’s rebels — unlike Pissarro — may choose to avoid making uninteresting subjects such as a slice of muddy road, a field of cabbages or a patch of sky into extraordinary art, the extraordinary art of reclaiming the commons continues, and it’s here — and not on the walls of a state and corporate-sponsored gallery — that you’ll find Pissarro’s true legacy.

::::::

[Camille Pissarro. The First Impressionist is at the NGV: International, St Kilda Road, from Saturday to May 28. Tickets: $18/$12/$45 family.]

How many stopped writing at thirty?

How many went to work for Time?

How many died of prefrontal

Lobotomies in the Communist Party?

How many are lost in the back wards

Of provincial madhouses?

How many on the advice of

Their psychoanalysts, decided

A business career was best after all?

How many are hopeless alcoholics?