[I once saw Thomas Frank LIVE! On October 1, 2002 @ Trades Hall to be exact. He was v funny.]

Thomas Frank

The Baffler

No.6, 1995

The public be damned! I work for my stockholders.

–William H. Vanderbilt, 1879

Break the rules. Stand apart. Keep your head. Go with your heart.

–TV commercial for Vanderbilt perfume, 1994

Capitalism is changing, obviously and drastically. From the moneyed pages of the Wall Street Journal to TV commercials for airlines and photocopiers we hear every day about the new order’s globe-spanning, cyber-accumulating ways. But our notion about what’s wrong with American life and how the figures responsible are to be confronted haven’t changed much in thirty years. Call it, for convenience, the “countercultural idea.” It holds that the paramount ailment of our society is conformity, a malady that has variously been described as over-organization, bureaucracy, homogeneity, hierarchy, logocentrism, technocracy, the Combine, the Apollonian. We all know what it is and what it does. It transforms humanity into “organization man,” into “the man in the gray flannel suit.” It is “Moloch whose mind is pure machinery,” the “incomprehensible prison” that consumes “brains and imagination.” It is artifice, starched shirts, tailfins, carefully mowed lawns, and always, always, the consciousness of impending nuclear destruction. It is a stiff, militaristic order that seeks to suppress instinct, to forbid sex and pleasure, to deny basic human impulses and individuality, to enforce through a rigid uniformity a meaningless plastic consumerism.

As this half of the countercultural idea originated during the 1950s, it is appropriate that the evils of conformity are most conveniently summarized with images of 1950s suburban correctness. You know, that land of sedate music, sexual repression, deference to authority, Red Scares, and smiling white people standing politely in line to go to church. Constantly appearing as a symbol of arch-backwardness in advertising and movies, it is an image we find easy to evoke.

The ways in which this system are to be resisted are equally well understood and agreed-upon. The Establishment demands homogeneity; we revolt by embracing diverse, individual lifestyles. It demands self-denial and rigid adherence to convention; we revolt through immediate gratification, instinct uninhibited, and liberation of the libido and the appetites. Few have put it more bluntly than Jerry Rubin did in 1970: “Amerika says: Don’t! The yippies say: Do It!” The countercultural idea is hostile to any law and every establishment. “Whenever we see a rule, we must break it,” Rubin continued. “Only by breaking rules do we discover who we are.” Above all rebellion consists of a sort of Nietzschean antinomianism, an automatic questioning of rules, a rejection of whatever social prescriptions we’ve happened to inherit. Just Do It is the whole of the law.

The patron saints of the countercultural idea are, of course, the Beats, whose frenzied style and merry alienation still maintain a powerful grip on the American imagination. Even forty years after the publication of On the Road, the works of Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs remain the sine qua non of dissidence, the model for aspiring poets, rock stars, or indeed anyone who feels vaguely artistic or alienated. That frenzied sensibility of pure experience, life on the edge, immediate gratification, and total freedom from moral restraint, which the Beats first propounded back in those heady days when suddenly everyone could have their own TV and powerful V-8, has stuck with us through all the intervening years and become something of a permanent American style. Go to any poetry reading and you can see a string of junior Kerouacs go through the routine, upsetting cultural hierarchies by pushing themselves to the limit, straining for that gorgeous moment of original vice when Allen Ginsberg first read “Howl” in 1955 and the patriarchs of our fantasies recoiled in shock. The Gap may have since claimed Ginsberg and USA Today may run feature stories about the brilliance of the beloved Kerouac, but the rebel race continues today regardless, with ever-heightening shit-references calculated to scare Jesse Helms, talk about sex and smack that is supposed to bring the electricity of real life, and ever-more determined defiance of the repressive rules and mores of the American 1950s–rules and mores that by now we know only from movies.

But one hardly has to go to a poetry reading to see the countercultural idea acted out. Its frenzied ecstasies have long since become an official aesthetic of consumer society, a monotheme of mass as well as adversarial culture. Turn on the TV and there it is instantly: the unending drama of consumer unbound and in search of an ever-heightened good time, the inescapable rock `n’ roll soundtrack, dreadlocks and ponytails bounding into Taco Bells, a drunken, swinging-camera epiphany of tennis shoes, outlaw soda pops, and mind-bending dandruff shampoos. Corporate America, it turns out, no longer speaks in the voice of oppressive order that it did when Ginsberg moaned in 1956 that Time magazine was

always telling me about responsibility. Business-

men are serious. Movie producers are serious.

Everybody’s serious but me.

Nobody wants you to think they’re serious today, least of all Time Warner. On the contrary: the Culture Trust is now our leader in the Ginsbergian search for kicks upon kicks. Corporate America is not an oppressor but a sponsor of fun, provider of lifestyle accoutrements, facilitator of carnival, our slang-speaking partner in the quest for that ever-more apocalyptic orgasm. The countercultural idea has become capitalist orthodoxy, its hunger for transgression upon transgression now perfectly suited to an economic-cultural regime that runs on ever-faster cyclings of the new; its taste for self-fulfillment and its intolerance for the confines of tradition now permitting vast latitude in consuming practices and lifestyle experimentation.

Consumerism is no longer about “conformity” but about “difference.” Advertising teaches us not in the ways of puritanical self-denial (a bizarre notion on the face of it), but in orgiastic, never-ending self-fulfillment. It counsels not rigid adherence to the tastes of the herd but vigilant and constantly updated individualism. We consume not to fit in, but to prove, on the surface at least, that we are rock `n’ roll rebels, each one of us as rule-breaking and hierarchy-defying as our heroes of the 60s, who now pitch cars, shoes, and beer. This imperative of endless difference is today the genius at the heart of American capitalism, an eternal fleeing from “sameness” that satiates our thirst for the New with such achievements of civilization as the infinite brands of identical cola, the myriad colors and irrepressible variety of the cigarette rack at 7-Eleven.

As existential rebellion has become a more or less official style of Information Age capitalism, so has the countercultural notion of a static, repressive Establishment grown hopelessly obsolete. However the basic impulses of the countercultural idea may have disturbed a nation lost in Cold War darkness, they are today in fundamental agreement with the basic tenets of Information Age business theory. So close are they, in fact, that it has become difficult to understand the countercultural idea as anything more than the self-justifying ideology of the new bourgeoisie that has arisen since the 1960s, the cultural means by which this group has proven itself ever so much better skilled than its slow-moving, security-minded forebears at adapting to the accelerated, always-changing consumerism of today. The anointed cultural opponents of capitalism are now capitalism’s ideologues.

The two come together in perfect synchronization in a figure like Camille Paglia, whose ravings are grounded in the absolutely noncontroversial ideas of the golden sixties. According to Paglia, American business is still exactly what it was believed to have been in that beloved decade, that is, “puritanical and desensualized.” Its great opponents are, of course, liberated figures like “the beatniks,” Bob Dylan, and the Beatles. Culture is, quite simply, a binary battle between the repressive Apollonian order of capitalism and the Dionysian impulses of the counterculture. Rebellion makes no sense without repression; we must remain forever convinced of capitalism’s fundamental hostility to pleasure in order to consume capitalism’s rebel products as avidly as we do. It comes as little surprise when, after criticizing the “Apollonian capitalist machine” (in her book, Vamps & Tramps), Paglia applauds American mass culture (in Utne Reader), the preeminent product of that “capitalist machine,” as a “third great eruption” of a Dionysian “paganism.” For her, as for most other designated dissidents, there is no contradiction between replaying the standard critique of capitalist conformity and repressiveness and then endorsing its rebel products–for Paglia the car culture and Madonna–as the obvious solution: the Culture Trust offers both Establishment and Resistance in one convenient package. The only question that remains is why Paglia has not yet landed an endorsement contract from a soda pop or automobile manufacturer.

Other legendary exponents of the countercultural idea have been more fortunate–William S. Burroughs, for example, who appears in a television spot for the Nike corporation. But so openly does the commercial flaunt the confluence of capital and counterculture that it has brought considerable criticism down on the head of the aging beat. Writing in the Village Voice, Leslie Savan marvels at the contradiction between Burroughs’ writings and the faceless corporate entity for which he is now pushing product. “Now the realization that nothing threatens the system has freed advertising to exploit even the most marginal elements of society,” Savan observes. “In fact, being hip is no longer quite enough–better the pitchman be `underground.'” Meanwhile Burroughs’ manager insists, as all future Cultural Studies treatments of the ad will no doubt also insist, that Burroughs’ presence actually makes the commercial “deeply subversive”–“I hate to repeat the usual mantra, but you know, homosexual drug addict, manslaughter, accidental homicide.” But Savan wonders whether, in fact, it is Burroughs who has been assimilated by corporate America. “The problem comes,” she writes, “in how easily any idea, deed, or image can become part of the sponsored world.”

The most startling revelation to emerge from the Burroughs/Nike partnership is not that corporate America has overwhelmed its cultural foes or that Burroughs can somehow remain “subversive” through it all, but the complete lack of dissonance between the two sides. Of course Burroughs is not “subversive,” but neither has he “sold out”: His ravings are no longer appreciably different from the official folklore of American capitalism. What’s changed is not Burroughs, but business itself. As expertly as Burroughs once bayoneted American proprieties, as stridently as he once proclaimed himself beyond the laws of man and God, he is today a respected ideologue of the Information Age, occupying roughly the position in the pantheon of corporate-cultural thought once reserved strictly for Notre Dame football coaches and positive-thinking Methodist ministers. His inspirational writings are boardroom favorites, his dark nihilistic burpings the happy homilies of the new corporate faith.

For with the assumption of power by Drucker’s and Reich’s new class has come an entirely new ideology of business, a way of justifying and exercising power that has little to do with the “conformity” and the “establishment” so vilified by the countercultural idea. The management theorists and “leadership” charlatans of the Information Age don’t waste their time prattling about hierarchy and regulation, but about disorder, chaos, and the meaninglessness of convention. With its reorganization around information, capitalism has developed a new mythology, a sort of corporate antinomianism according to which the breaking of rules and the elimination of rigid corporate structure have become the central article of faith for millions of aspiring executives.

Dropping Naked Lunch and picking up Thriving on Chaos, the groundbreaking 1987 management text by Tom Peters, the most popular business writer of the past decade, one finds more philosophical similarities than one would expect from two manifestos of, respectively, dissident culture and business culture. If anything, Peters’ celebration of disorder is, by virtue of its hard statistics, bleaker and more nightmarish than Burroughs’. For this popular lecturer on such once-blithe topics as competitiveness and pop psychology there is nothing, absolutely nothing, that is certain. His world is one in which the corporate wisdom of the past is meaningless, established customs are ridiculous, and “rules” are some sort of curse, a remnant of the foolish fifties that exist to be defied, not obeyed. We live in what Peters calls “A World Turned Upside Down,” in which whirl is king and, in order to survive, businesses must eventually embrace Peters’ universal solution: “Revolution!” “To meet the demands of the fast-changing competitive scene,” he counsels, “we must simply learn to love change as much as we have hated it in the past.” He advises businessmen to become Robespierres of routine, to demand of their underlings, “`What have you changed lately?’ `How fast are you changing?’ and `Are you pursuing bold enough change goals?'” “Revolution,” of course, means for Peters the same thing it did to Burroughs and Ginsberg, Presley and the Stones in their heyday: breaking rules, pissing off the suits, shocking the bean-counters: “Actively and publicly hail defiance of the rules, many of which you doubtless labored mightily to construct in the first place.” Peters even suggests that his readers implement this hostility to logocentrism in a carnivalesque celebration, drinking beer out in “the woods” and destroying “all the forms and rules and discontinued reports” and, “if you’ve got real nerve,” a photocopier as well.

Today corporate antinomianism is the emphatic message of nearly every new business text, continually escalating the corporate insurrection begun by Peters. Capitalism, at least as it is envisioned by the best-selling management handbooks, is no longer about enforcing Order, but destroying it. “Revolution,” once the totemic catchphrase of the counterculture, has become the totemic catchphrase of boomer-as-capitalist. The Information Age businessman holds inherited ideas and traditional practices not in reverence, but in high suspicion. Even reason itself is now found to be an enemy of true competitiveness, an out-of-date faculty to be scrupulously avoided by conscientious managers. A 1990 book by Charles Handy entitled The Age of Unreason agrees with Peters that we inhabit a time in which “there can be no certainty” and suggests that readers engage in full-fledged epistemological revolution: “Thinking Upside Down,” using new ways of “learning which can … be seen as disrespectful if not downright rebellious,” methods of approaching problems that have “never been popular with the upholders of continuity and of the status quo.” Three years later the authors of Reengineering the Corporation (“A Manifesto for Business Revolution,” as its subtitle declares) are ready to push this doctrine even farther. Not only should we be suspicious of traditional practices, but we should cast out virtually everything learned over the past two centuries!

Business reengineering means putting aside much of the received wisdom of two hundred years of industrial management. It means forgetting how work was done in the age of the mass market and deciding how it can best be done now. In business reengineering, old job titles and old organizational arrangements–departments, divisions, groups, and so on–cease to matter. They are artifacts of another age.

As countercultural rebellion becomes corporate ideology, even the beloved Buddhism of the Beats wins a place on the executive bookshelf. In The Leader as Martial Artist (1993), Arnold Mindell advises men of commerce in the ways of the Tao, mastery of which he likens, of course, to surfing. For Mindell’s Zen businessman, as for the followers of Tom Peters, the world is a wildly chaotic place of opportunity, navigable only to an enlightened “leader” who can discern the “timespirits” at work behind the scenes. In terms Peters himself might use were he a more more meditative sort of inspiration professional, Mindell explains that “the wise facilitator” doesn’t seek to prevent the inevitable and random clashes between “conflicting field spirits,” but to anticipate such bouts of disorder and profit thereby.

Contemporary corporate fantasy imagines a world of ceaseless, turbulent change, of centers that ecstatically fail to hold, of joyous extinction for the craven gray-flannel creature of the past. Businessmen today decorate the walls of their offices not with portraits of President Eisenhower and emblems of suburban order, but with images of extreme athletic daring, with sayings about “diversity” and “empowerment” and “thinking outside the box.” They theorize their world not in the bar car of the commuter train, but in weepy corporate retreats at which they beat their tom-toms and envision themselves as part of the great avant-garde tradition of edge-livers, risk-takers, and ass-kickers. Their world is a place not of sublimation and conformity, but of “leadership” and bold talk about defying the herd. And there is nothing this new enlightened species of businessman despises more than “rules” and “reason.” The prominent culture-warriors of the right may believe that the counterculture was capitalism’s undoing, but the antinomian businessmen know better. “One of the t-shirt slogans of the sixties read, `Question authority,'” the authors of Reengineering the Corporation write. “Process owners might buy their reengineering team members the nineties version: `Question assumptions.'”

The new businessman quite naturally gravitates to the slogans and sensibility of the rebel sixties to express his understanding of the new Information World. He is led in what one magazine calls “the business revolution” by the office-park subversives it hails as “business activists,” “change agents,” and “corporate radicals.” He speaks to his comrades through commercials like the one for “Warp,” a type of IBM computer operating system, in which an electric guitar soundtrack and psychedelic video effects surround hip executives with earrings and hairdos who are visibly stunned by the product’s gnarly ‘tude (It’s a “totally cool way to run your computer,” read the product’s print ads). He understands the world through Fast Company, a successful new magazine whose editors take their inspiration from Hunter S. Thompson and whose stories describe such things as a “dis-organization” that inhabits an “anti-office” where “all vestiges of hierarchy have disappeared” or a computer scientist who is also “a rabble rouser, an agent provocateur, a product of the 1960s who never lost his activist fire or democratic values.” He is what sociologists Paul Leinberger and Bruce Tucker have called “The New Individualist,” the new and improved manager whose arty worldview and creative hip derive directly from his formative sixties days. The one thing this new executive is definitely not is Organization Man, the hyper-rational counter of beans, attender of church, and wearer of stiff hats. In television commercials, through which the new American businessman presents his visions and self-understanding to the public, perpetual revolution and the gospel of rule-breaking are the orthodoxy of the day. You only need to watch for a few minutes before you see one of these slogans and understand the grip of antinomianism over the corporate mind:

Sometimes You Gotta Break the Rules –Burger King

If You Don’t Like the Rules, Change Them –WXRT-FM

The Rules Have Changed –Dodge

The Art of Changing –Swatch

There’s no one way to do it. –Levi’s

This is different. Different is good. –Arby’s

Just Different From the Rest –Special Export beer

The Line Has Been Crossed: The Revolutionary New Supra –Toyota

Resist the Usual –the slogan of both Clash Clear Malt and Young & Rubicam

Innovate Don’t Imitate –Hugo Boss

Chart Your Own Course –Navigator Cologne

It separates you from the crowd –Vision Cologne

In most, the commercial message is driven home with the vanguard iconography of the rebel: screaming guitars, whirling cameras, and startled old timers who, we predict, will become an increasingly indispensable prop as consumers require ever-greater assurances that, Yes! You are a rebel! Just look at how offended they are!

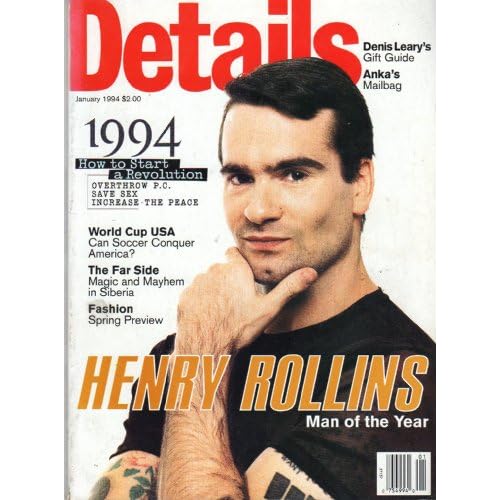

Our businessmen imagine themselves rebels, and our rebels sound more and more like ideologists of business. Henry Rollins, for example, the maker of loutish, overbearing music and composer of high-school-grade poetry, straddles both worlds unproblematically. Rollins’ writing and lyrics strike all the standard alienated literary poses: He rails against overcivilization and yearns to “disconnect.” He veers back and forth between vague threats toward “weak” people who “bring me down” and blustery declarations of his weightlifting ability and physical prowess. As a result he ruled for several years as the preeminent darling of Details magazine, a periodical handbook for the young executive on the rise, where rebellion has achieved a perfect synthesis with corporate ideology. In 1992 Details named Rollins a “rock `n’ roll samurai,” an “emblem … of a new masculinity” whose “enlightened honesty” is “a way of being that seems to flesh out many of the ideas expressed in contemporary culture and fashion.” In 1994 the magazine consummated its relationship with Rollins by naming him “Man of the Year,” printing a fawning story about his muscular worldview and decorating its cover with a photo in which Rollins displays his tattoos and rubs his chin in a thoughtful manner.

Details found Rollins to be such an appropriate role model for the struggling young businessman not only because of his music-product, but because of his excellent “self-styled identity,” which the magazine describes in terms normally reserved for the breast-beating and soul-searching variety of motivational seminars. Although he derives it from the quality-maximizing wisdom of the East rather than the unfashionable doctrines of Calvin, Rollins’ rebel posture is identical to that fabled ethic of the small capitalist whose regimen of positive thinking and hard work will one day pay off. Details describes one of Rollins’ songs, quite seriously, as “a self-motivational superforce, an anthem of empowerment,” teaching lessons that any aspiring middle-manager must internalize. Elsewhere, Iggy Pop, that great chronicler of the ambitionless life, praises Rollins as a “high achiever” who “wants to go somewhere.” Rollins himself even seems to invite such an interpretation. His recent spoken-word account of touring with Black Flag, delivered in an unrelenting two-hour drill-instructor staccato, begins with the timeless bourgeois story of opportunity taken, of young Henry leaving the security of a “straight job,” enlisting with a group of visionaries who were “the hardest working people I have ever seen,” and learning “what hard work is all about.” In the liner notes he speaks proudly of his Deming-esque dedication to quality, of how his bandmates “Delivered under pressure at incredible odds.” When describing his relationship with his parents for the readers of Details, Rollins quickly cuts to the critical matter, the results that such dedication has brought: “Mom, Dad, I outgross both of you put together,” a happy observation he repeats in his interview with the New York Times Magazine.

Despite the extreme hostility of punk rockers with which Rollins had to contend all through the 1980s, it is he who has been chosen by the commercial media as the godfather of rock `n’ roll revolt. It is not difficult to see why. For Rollins the punk rock decade was but a lengthy seminar on leadership skills, thriving on chaos, and total quality management. Rollins’ much-celebrated anger is indistinguishable from the anger of the frustrated junior executive who finds obstacles on the way to the top. His discipline and determination are the automatic catechism of any small entrepreneur who’s just finished brainwashing himself with the latest leadership and positive-thinking tracts; his poetry is the inspired verse of 21 Days to Unlimited Power or Let’s Get Results, Not Excuses. Henry Rollins is no more a threat to established power in America than was Dale Carnegie. And yet Rollins as king of the rebels–peerless and ultimate–is the message hammered home wherever photos of his growling visage appears. If you’re unhappy with your lot, the Culture Trust tells us with each new tale of Rollins, if you feel you must rebel, take your cue from the most disgruntled guy of all: Lift weights! Work hard! Meditate in your back yard! Root out the weaknesses deep down inside yourself! But whatever you do, don’t think about who controls power or how it is wielded.

* * *

The structure and thinking of American business have changed enormously in the years since our popular conceptions of its problems and abuses were formulated. In the meantime the mad frothings and jolly apolitical revolt of Beat, despite their vast popularity and insurgent air, have become powerless against a new regime that, one suspects, few of Beat’s present-day admirers and practitioners feel any need to study or understand. Today that beautiful countercultural idea, endorsed now by everyone from the surviving Beats to shampoo manufacturers, is more the official doctrine of corporate America than it is a program of resistance. What we understand as “dissent” does not subvert, does not challenge, does not even question the cultural faiths of Western business. What David Rieff wrote of the revolutionary pretensions of multiculturalism is equally true of the countercultural idea: “The more one reads in academic multiculturalist journals and in business publications, and the more one contrasts the speeches of CEOs and the speeches of noted multiculturalist academics, the more one is struck by the similarities in the way they view the world.” What’s happened is not co-optation or appropriation, but a simple and direct confluence of interest.

The problem with cultural dissent in America isn’t that it’s been co-opted, absorbed, or ripped-off. Of course it’s been all of these things. But it has proven so hopelessly susceptible to such assaults for the same reason it has become so harmless in the first place, so toothless even before Mr. Geffen’s boys discover it angsting away in some bar in Lawrence, Kansas: It is no longer any different from the official culture it’s supposed to be subverting. The basic impulses of the countercultural idea, as descended from the holy Beats, are about as threatening to the new breed of antinomian businessmen as Anthony Robbins, selling success & how to achieve it on a late-night infomercial.

The people who staff the Combine aren’t like Nurse Ratched. They aren’t Frank Burns, they aren’t the Church Lady, they aren’t Dean Wormer from Animal House, they aren’t those repressed old folks in the commercials who want to ban Tropicana Fruit Twisters. They’re hipper than you can ever hope to be because hip is their official ideology, and they’re always going to be there at the poetry reading to encourage your “rebellion” with a hearty “right on, man!” before you even know they’re in the auditorium. You can’t outrun them, or even stay ahead of them for very long: it’s their racetrack, and that’s them waiting at the finish line to congratulate you on how outrageous your new style is, on how you shocked those stuffy prudes out in the heartland.

See also : ‘On the Poverty of Hip Life’, Contradiction, April 1972.

Brilliant stuff. I hope all those “political activists” who think that “sticking it to the Man” just means living a cool lifestyle and having the kind of sex they want read this, and choke on it.

[Seriously d00d…]