WSF Caracas: Shroud for Venezuela’s social movements

A member of the group promoting the Alternative Social Forum explains why the World Social Forum (WSF), taking place in Caracas during January 2006, is another attempt by the Chavez government to impede the autonomous development of social struggles in the country.

::

During the week of January 24 to 29, 2006 the polycentric version of the VI World Social Forum as well as the II Social Forum of the Americas will take place in Caracas. The event has generated great expectations since this city is the epicenter of what since 1999 has been known as the “Bolivarian Revolution”, with much impact in Latin America and wide popularity among diverse social and left movements in the world. The fact that Venezuela is the second continental seat of the WSF is a tacit backing of the governmental performance of President Hugo Chavez, as happened at the time with the local government of the Workers Party in Porto Alegre during its slow but true climb to the presidential chair. Is this backing of the government related to the actual strength of the social movements of Venezuela? Or, to say in different words, what contributions the WSF in Caracas will make towards the process of consolidation, expansion and articulation of the country’s social movements? To answer this question we will first make a brief review of the nation’s contemporary history.

“Punto Fijo” and “Caracazo”

After decades of military and strong man dictatorships, in 1958 a new democratic period is inaugurated in Venezuela. The so called Pact of Punto Fijo is made among the principal dominating actors, who agree to alternate the main political parties of that era, Democratic Action and COPEI, in power. A few years later a period of armed struggle by the insurgent left starts, a chapter lasting less than a decade with the progressive incorporation of these actors into the “legal” and parliamentary politics, motivated by, among other things, the social floor built by the social-democracy thanks to the large income from oil. The royalties of black gold allow for democratic stability unknown in the continent, paying for a generous social security, widespread education at all levels and subsidizing labor unions and trade associations all over the territory. The oil tanker that daily filled their hulls at the Venezuelan ports financed the ample middle class that developed during the decades of the 60’s and 70’s, reaching its climax with the so-called nationalization of oil that happened in 1976, when transnational corporations such as Shell stopped operating in the country. From that year until the end of 1981 it was the period known as the fat cows due to the huge amount of money that came into the national treasury. At the beginning of 1983 the devaluation of the currency, the bolivar, is announced, and a period of economic crises begins that initiates the break up of this governmental model started in 1958. During the mid 80’s large popular mobilizations start but do not translate into votes for the left political parties which historically maintain a percentage around 5%.

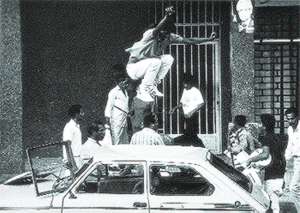

The most notable expression of the death throes of the Pact of the Punto Fijo happens in February 1989, during the so called “Caracazo”, when hundreds of businesses were looted in different cities in a week of violent popular explosions, brutally repressed by the army, with a number of deaths and disappearances still unknown, which some say is over a thousand. It is from that February that a civil society, outside the established political parties and with no client relationship to the state, begins to take form. To name but a few, we find the first human rights organizations, ecological associations and networks that promote the Environmental Penal Law and the social initiatives that fueled the mobilizations against the neo-liberal “package” of Carlos Andres Perez -– then president of Venezuela –- which constitute examples of what autonomous social struggle were possible in that context when political parties and other upholders of the government showed clear signs of fatigue.

The most notable expression of the death throes of the Pact of the Punto Fijo happens in February 1989, during the so called “Caracazo”, when hundreds of businesses were looted in different cities in a week of violent popular explosions, brutally repressed by the army, with a number of deaths and disappearances still unknown, which some say is over a thousand. It is from that February that a civil society, outside the established political parties and with no client relationship to the state, begins to take form. To name but a few, we find the first human rights organizations, ecological associations and networks that promote the Environmental Penal Law and the social initiatives that fueled the mobilizations against the neo-liberal “package” of Carlos Andres Perez -– then president of Venezuela –- which constitute examples of what autonomous social struggle were possible in that context when political parties and other upholders of the government showed clear signs of fatigue.

1989 represented an important moment in the history of the autonomous social organization of popular demands. The effervescence apparent before and after the popular revolt shows the seams of a social fabric made up of infinite socio-political initiatives, with different and growing levels of articulation among themselves. They take aim against the president and his policy of “the big turn”: his attempt to apply the neo-liberal prescription dictated by the International Monetary Fund which contrasted with the populist policies imposed by previous governments. In this scenario of growing citizen mobilization something never seen before takes place: the Attorney General of the Republic opens a case against the president for corruption and misappropriation of the so called “secret parties”. In May 1993 Perez was suspended from his functions.

Chavez and his movement

A year before the president’s fall due to charges of corruption, a political recourse that seemed to be relegated to the past came back to the front pages of the press: the coup d’etat. From the years 1899 to 1958, five conspiracies headed by the military forced the change of the first president, paradoxically including one that in 1945 claimed to be in the name of democracy and the parties system.

Military insubordination in order to take power wasn’t the exclusive patrimony of sectors identified with the right. Several armed insurrections stimulated by the Marxist-Leninist left spoke of the “civil-military alliance”, in which political vanguards linked with “progressive sectors of the armed forces” to provoke change. This appeal to a pretended progressiveness of the Venezuelan army interpreted its multi-class character under dialectical materialism, attempting to exacerbate the “class contradictions” between soldiers and officers to “win them over to the socialist cause”. It is true that the popular heterogeneity of the Venezuelan army is different from the elitist conformation of other armies in the continent, but the Marxist reductionism forgot that its hierarchical and value systems educated them to see themselves as a class different from the civilians. On the other hand, the Venezuelan army was also formed in the anti-communism and the fight against subversion according to the dictates of the Southern Command of the United States, as part of the logic of the Cold War.

Military insubordination in order to take power wasn’t the exclusive patrimony of sectors identified with the right. Several armed insurrections stimulated by the Marxist-Leninist left spoke of the “civil-military alliance”, in which political vanguards linked with “progressive sectors of the armed forces” to provoke change. This appeal to a pretended progressiveness of the Venezuelan army interpreted its multi-class character under dialectical materialism, attempting to exacerbate the “class contradictions” between soldiers and officers to “win them over to the socialist cause”. It is true that the popular heterogeneity of the Venezuelan army is different from the elitist conformation of other armies in the continent, but the Marxist reductionism forgot that its hierarchical and value systems educated them to see themselves as a class different from the civilians. On the other hand, the Venezuelan army was also formed in the anti-communism and the fight against subversion according to the dictates of the Southern Command of the United States, as part of the logic of the Cold War.

After 34 years without military conspiracies – one of the premises of the Pact of Punto Fijo – in 1992 a large group of middle rank army officers attempts a coup d’etat against Carlos Andres Perez. On TV, a character in uniform unknown to all announced the defeat of the uprising “for the time being”. That officer was Hugo Chavez, who spend some years arrested for military mutiny and was set free, via pardon, by the next elected president: Rafael Caldera, who, like Perez, was in power for the second time.

After 34 years without military conspiracies – one of the premises of the Pact of Punto Fijo – in 1992 a large group of middle rank army officers attempts a coup d’etat against Carlos Andres Perez. On TV, a character in uniform unknown to all announced the defeat of the uprising “for the time being”. That officer was Hugo Chavez, who spend some years arrested for military mutiny and was set free, via pardon, by the next elected president: Rafael Caldera, who, like Perez, was in power for the second time.

Chavez liberation, which happened during the mid 90’s, took place amid large mass mobilization and consciousness rising. For the first time a presidential candidate from the non-traditional sectors, Andres Velasquez, got to improve on the historical 5% of the left, placing himself very close to the elected candidate in percentage points. This was symptomatic of the will for change that like an epidemic grew among Venezuelans faced with the economic crisis and the fatigue of the democratic system. Chavez and his movement piggy back on that dynamic giving it a face to the unhappiness, thanks to the media magnification and its insurrectional aura. We repeat: a development that qualitatively and quantitatively is contemporary to Chavez’s movement and of which the MBR-200 (the name of Chavez’s first political group) was only a part. The paratrooper from Sabaneta makes a cynical and pragmatic reading of this reality, going from his militant abstention, during which time he was able to get the sympathy of many grass roots social movements, to the presidential candidature, and let’s not forget, with the support of the mass media and the financing from sectors of international capital. Chavez and his charismatic dominion convince many sectors that he represents the vanguard of the struggle against the binomial AD-COPEI and is a project for revolutionary transformation. The shortsightedness of the traditional parties and their own mummification accelerated their final crisis, partially masked by the media show of the events of 2002 but that sooner rather than later –as indeed happened – would end up dismantling the empty shells of such parties.

Institutionalizing rebellion

We were saying Chavez rides on a wave of popular unhappiness that in 1989 started weaving a social fabric made up of infinity of embryonic organizations, with different but growing levels of mutual articulation. One of the virtues of chavism is gathering diverse demands and incorporating them in its diffuse ideology giving the sensation that bolivarianism was a legitimate expression of the left’s and the community’s will. The next step was the establishment of an uncontestable direction, paradoxically spreading a democratic proposal of “participation” and the imposition upon its grass root basis of an agenda decided at the top, basically limited to re-legitimization at the ballot. This way the social movements already spent due to their progressive incorporation in the cumulative politico-electoral logic are mortgaging their own autonomy, and even more important, to the imposition of an authoritarian model of domination, becoming immobilized to raise their own demands. It is in the imposition of organizational models directed by a single hand and in the dismantling of citizen’s initiatives that preceded it that one finds the key to understand the current fragmentation of the social movements in Venezuela.

Whoever watches from the outside the avalanche of revolutionary propaganda financed by the Venezuelan state may well be astonished by this statement. Out of the many examples that support it let’s name one key fact. During the 90’s the management of the state’s hydrocarbon company, Pdvsa, attempted to lobby around a policy of opening up the oil trade in order to involve transnational companies in the exploration and exploitation of new wells, reversing the nationalization of 1976. The proposal, in agreement with free market policies, generated widespread and rabid resistance in many sectors, rendering it politically inapplicable. Behind the revolutionary and anti-imperialist rhetoric centered mainly on George Bush Jr., President Chavez has signed off on the largest concessions of energy resources since the decade of the 40’s with no internal opposition. For example, the largest natural gas reserve in the country, the Delta Platform, has been given in concession to Chevron, Conoco-Phillips and Statoil for periods of over 30 years. From January 1, 2006 on, mixed enterprises between the multinationals and the state’s oil company will be in force, both parts being partners in the exploration and commercial development of the reserves. As of this writing, December 2005, there had been no mobilization by any sector against this measure. Pablo Hernandez Parra, an oil expert and collaborator with the web site www.soberania.org says in one of his articles in the press: “The essence of all that’s happening in this new Macondo called Venezuela is just the fact that national and international capital headed by oil companies have donned the red beret and sash, and advancing with triumphant strides impose their privatization program under the guise of socialism for the XXI century. Everything that happens today in this country, from the oil policy to the media circus with land expropriations, is nothing more than a vulgar show between the puppets of capital: government and opposition, in order to consolidate the process of privatization of the natural resources of the nation: oil, gas, mines, land, for the exclusive benefit of big capital.”

The World Social Forum

In the last four years Venezuela has undergone a polarization induced by the top players vying for power: the old “punto fijista” bureaucracy (Fedecamaras, CTV, political parties) against the new Chavez bureaucracy that has supplanted the previous one. This antagonism, false inasmuch as real vs. pretended exercise of power, sustained and amplified by the media, has benefited those who have cast themselves as legitimate voices of the sector of Venezuelan society they claim to represent. Part of the demobilization of the social movements answers to this logic: having taken part in, and assumed blindly the political agenda imposed from above, postponing their own claims. Another chapter belongs to the expectations created by some of the social activists faced with a “progressive and left” government, spokesmen of a discourse that assumes the language of the movements but whose policies go in the opposite direction.

The former U.S. ambassador to Venezuela, John Maisto, told the press: “Chavez has to be evaluated by what he does, not by what he says”. This explains why in spite of diplomatic bruising, Venezuela makes her best deals with the most dynamic sectors of global capitalism, including the Big Brother from the North, which consumes over 60% of the energy exports leaving our ports. Here we need to clarify that international geopolitics is radically different from that of the Cold War. As long as countries keep to their roles assigned by economic globalization, they can have the local politics they like best. This is precisely the Venezuelan case not only on oil and energy matters – counting on more than $60 a barrel, the highest prices ever – but also in the most dynamic sectors of the world’s economy: banks, finances and telecommunications. Also, remember that Caracas continues to be a punctual payer of its external debt and obeys without any flack the obligations contracted with the IMF.

This is the context in which the World Social Forum will take place in these shores of the Caribbean: with demobilized local social movements and with no freedom of action, with a government that will finance it and even brags about it in advertisements and press conferences, at the beginning of a year of presidential elections and with the tribune of the WSF as the ideal starting point in the electoral campaign. The lack of operative social networks and infrastructure of citizen’s initiative, the event’s logistics: room and board, transportation, will be done by the Venezuelan army for the lesser delegations and by the Hilton hotel chain for those of higher strategic importance for the national executive, as has been the tradition in previous “revolutionary” councils in Caracas. As a movement Chavism – where the main spokespeople of the committee promoting the WSF in Caracas belong – in seven years has only recognized as players those who submit to the leadership of Hugo Chavez, therefore his declarations regarding the realization of a pluralistic forum sound like demagogic speech for the peanut gallery. In this sense, this event will deepen the current dispersal of social elements and will not, in our opinion, change anything.

Because of this and in spite of all the difficulties, of the lack of resources and infrastructure and the asymmetry, a group of us believe it’s necessary to have an event parallel to the WSF (in the same city and during the same days) to insure that energy policy discussions, concentration of power, militarism, autonomy and new social movements, the model for the development of the mine industry and the environment, alternative communications and counter-power will take place opening the possibility to spread other versions of what’s happening in Venezuela. To this we add the degradation experienced by the WSF: it being controlled by NGO’s and sanitized social groups such as ATTAC and Greenpeace, as well as the manipulation by left political parties as platforms for propaganda. Besides, the Latin American situation opens up new agendas for discussion which we feel will not be sufficiently considered at the WSF: the fact that several South American governments are “left” and how their social policies have been incapable of reducing poverty, promote structural changes, preserve the environment and safeguard the rights of minorities, since they limit themselves to capitalism with a human face. We think our event, the Alternative Social Forum (ASF) can be one of the many necessary spaces for gathering and dialog among different grass roots movements, in order to establish our claims and elaborate our agenda of events and mobilizations, without interference from anybody outside its own dynamic. Therefore we invite all activists to visit Venezuela in this fourth week of January to participate whether in the WSF or the ASF, and, most importantly, to see with their own eyes the reality of this country, to contrast versions and data and stop interpreting things listening exclusively to the propaganda manufactured by the Venezuelan state or the opposition political parties.

Because of this and in spite of all the difficulties, of the lack of resources and infrastructure and the asymmetry, a group of us believe it’s necessary to have an event parallel to the WSF (in the same city and during the same days) to insure that energy policy discussions, concentration of power, militarism, autonomy and new social movements, the model for the development of the mine industry and the environment, alternative communications and counter-power will take place opening the possibility to spread other versions of what’s happening in Venezuela. To this we add the degradation experienced by the WSF: it being controlled by NGO’s and sanitized social groups such as ATTAC and Greenpeace, as well as the manipulation by left political parties as platforms for propaganda. Besides, the Latin American situation opens up new agendas for discussion which we feel will not be sufficiently considered at the WSF: the fact that several South American governments are “left” and how their social policies have been incapable of reducing poverty, promote structural changes, preserve the environment and safeguard the rights of minorities, since they limit themselves to capitalism with a human face. We think our event, the Alternative Social Forum (ASF) can be one of the many necessary spaces for gathering and dialog among different grass roots movements, in order to establish our claims and elaborate our agenda of events and mobilizations, without interference from anybody outside its own dynamic. Therefore we invite all activists to visit Venezuela in this fourth week of January to participate whether in the WSF or the ASF, and, most importantly, to see with their own eyes the reality of this country, to contrast versions and data and stop interpreting things listening exclusively to the propaganda manufactured by the Venezuelan state or the opposition political parties.

Facts on the paralysis of the Venezuelan social movements:

* Mobilizations in solidarity with the direct action done by the indigenous Pemon people (Gran Sabana) against the electrical transmission line to Brazil at the beginnings of 2001: None.

* The largest demonstration against the war in Iraq: Gathering at Plaza Venezuela, Caracas, 1200 people, May 25, 2003.

* Are there independent media centers, Indymedia in Venezuela? No

* Attendees at the demonstration before the Supreme Court of Justice by women’s groups protesting the release of the accused for the physical attack of Linda Loayza, October 26 2004: 80 people.

* Attendees at the national march against carbon exploitation in the state of Zulia, March 31 2005: 1000 people.

* Attendees at the demonstration called by the Bari, Yukpa and Wayuu peoples on October 11 2005 at Plaza Bolivar against carbon exploitation in the state of Zulia: 150 people.

* Mobilizations against the energy concessions by the government to multinational companies: None.

* Mobilizations against the governmental regulation of the largest forest in the country, Imataca, for mine and lumber exploitation: None.

* Mobilizations against the deplorable state of the hospitals in the country: None.

* Audiovisual productions the from a Chavist position denounce the contradictions between what the government says and what it does: One, “Our oil and other tales” (2004) by the Italians Gabrielle Muzio, Max Pugh and others, censored by the government. The TV stations Telesur, Canal 8 and Vive TV show previous productions from this audiovisual collective, but don’t show this last one.

* Any other direct action called by popular movements? On October 12, 2004 about one hundred activists from Chavist grass roots organizations gathered in front of a statue of Columbus in Plaza Venezuela to tear it down. During the convocation they expressed their desire to “take the head to Chavez” who at the time was at a function in the Teatro Teresa Carreño. Three activists were arrested for the destruction of the statue. On October 21 50 people demonstrated in front of the Court demanding the release of those arrested. A year later, according to writer Luis Britto Garcia, one of them continued in prison.

Rafael Uzcategui

===================

* El Libertario is a journal of an anarchist collective in Venezuela

_______________________________________________

A-infos-en mailing list

[email protected]