The people at the Danish Consulate & Embassy in Egypt are nice.

Last week, I sent them an email requesting confirmation that the Danish Ambassador to Egypt, Bjarne Sørensen, had indeed read an issue of Al Fagr at the time it was published. I received the following reply:

Dear Mr. Andy,

In reply to your question in email dated 17 February 2006 of how Ambassador Sørensen knew that the cartoons were published in October 2005; the Ambassador saw the 6 cartoons in Al Fagr on 17.10.2005.

Yours sincerely,

Vicki Hamza

A straight-forward answer to a straight-forward question.

So much for ‘Uncle Al’. Now for ‘Aunty Paul’.

Two weeks ago, Paul Reynolds, ‘World Affairs correspondent’ for the BBC News website, wrote a piece on blogging for the BBC titled Bloggers: an army of irregulars. Hundreds (if not thousands) of others in the blogosphere have already responded to Reynolds’ article, each in their own unique fashion, but what the hell: I gotta bone to pick with Paul, so here are some comments of my own.

For many in the “mainstream media”, as bloggers call us, weblogs are at best a nuisance and at worst dangerous. They are seen as the rantings and ravings either of the unbalanced or the tedious. My experience over the past few months has led me to an opposite conclusion. I regard the blogosphere as a source of criticism that must be listened to and as a source of information that can be used. The mainstream media (MSM in the jargon) has to sit up and take notice and develop some policies to meet this challenge. Most big organisations, whether in news or in business, have no policy towards blogs. They might, as the BBC has, develop a policy towards their own employees setting up such sites (no political opinions etc), but they have nobody monitoring the main blogs and have little idea how to respond to any criticism on them.

For many anarchist bloggers, corporate/state control over information flows (which employees of such conglomerations of economic and political power tend to delude themselves constitutes ‘the mainstream’) tends to function as little more than another mechanism for the reproduction of capitalist ideology. Such ideology is replete with the generally tedious and, by definition, unbalanced rantings and ravings of a literal army of concerned liberals, as well as sadistic reactionaries, and perhaps even one or two points in-between. Nevertheless, the corporate/state media also functions as a source of information that can be used by anarchists (and others!) as more than just a guide to the latest trends in consumption. The BBC’s Colombus-like discovery of the blogosphere, and the emerging though necessarily stunted realisation that this new form of media may well have serious repercussions for the corporate/state media industry, is thus useful for the insight it gives, both into the ideological workings of dominant institutions such as the BBC, but also the thinking of the class it serves.

Reynolds’ seperates his military analysis into three divisions. First, blogs as alternative source for news and information. Secondly, blogs as social power. Finally, blogs as political polemic.

1) Raw material

This portion is fairly straight-forward: Reynolds the journalist has found blogs a useful source of ‘news’. Interestingly, much of the raw material that Reynolds exploits is produced by critical assessment of government and business propaganda. Criticism such as this is, obviously, hardly new (and even more rarely ‘news’). What is novel is that the Internet, and blogging, allows individuals who possess such extraordinary talents (which is almost everyone) to make their critiques directly, immediately, and — crucially — very cheaply available, and to a theoretically vast audience. In other words, in this model, the forms of mediation of knowledge that the media represents are circumvented, and new flows of information allowed to circulate. In doing so, the Internet is functioning precisely as it was designed to, only instead of military data being circulated between geographically isolated US military installations, a truly vast range of human experience, thought and emotion is circulated between hundreds of millions of ‘users’ (that is, human beings).

In support of his argument that blogs constitute a useful resource for journalists, Reynolds lists a number of examples, “examples [which] show the collective strength of blogs”. One helped him to conclude that “blame should be shared at all levels of government” for the inept handling of emergency relief efforts following Hurricane Katrina. Another that the Pentagon was lying when it denied the use of white phosphorus as a weapon by the US military in Iraq. Why such a useful resource? And who are these bloggers anyway? According to Reynolds:

They have an army of what Sherlock Holmes called his “Baker Street Irregulars,” that is an almost unlimited number of people around the world, many of them expert on the subject under discussion, scouring sources and sending information in to an easily accessible central site which can disseminate it instantly.

Reynolds is here presumably referring to Daily Kos, a ‘liberal’ Democrat blog. As a model of blogging, it’s interesting, but not typical I suspect. As for the remarkable ability of expert liberal bloggers to “scoure… sources and send… information in to an easily accessible central site which can disseminate it instantly”…

On Staying Informed and Intellectual Self-Defense

By Noam Chomsky

There’s no way to be informed without devoting effort to the task, whether we have in mind what’s happening in the world, physics, major league baseball, or anything else. Understanding doesn’t come free. It’s true that the task is somewhere between awfully difficult and utterly hopeless for an isolated individual. But it’s feasible for anyone who is part of a cooperative community — and that’s true about all of the other cases too. Same holds for “intellectual self-defense.” It takes a lot of self-confidence — perhaps more self-confidence than one ought to have — to take a position alone because it seems to you right, in opposition to everything you see and hear. There’s even evidence about this: under experimental conditions people deny what they know to be true when they are informed that others they have reason to trust are doing so (Solomon Asch‘s classic experiments in social psychology, which were often held to show that people are conformist and irrational, but can be understood differently, to indicate that people are quite reasonable, and using all the information at hand).

More important than any of this is that a community — an organization — can be a basis for action, and while understanding the world may be good for the soul (not meant to be disparaging), it doesn’t help anyone else, or oneself very much either for that matter, unless it leads to action. There are also many techniques for penetrating the veil of propaganda that should become second nature in dealing with the output of doctrinal institutions (media, journals of opinion, scholarship). For example, it is quite common for the basic framework of an article or news report to be hopelessly misleading, conforming to doctrinal requirements. But within it one can often discover hints that something else is going on. I often recommend reading the mainstream press beginning with the final paragraphs. That’s no joke. The headline, the framing, the initial paragraphs, are designed (consciously — you learn these things in journalism school) to give the general picture, and the whole story for almost all readers, who aren’t going to take the trouble to look at the small print, to think much about it, and to compare it with yesterday’s tales. One discovers this all the time.

Of course, another story Reynolds refers to in his article as providing evidence of the useful role of bloggers in verifying stories is that concerning Al Fagr. “I also have to say that bloggers found out that the Danish cartoons were in fact published in an Egyptian newspaper last October. See link to WorldNetDaily on the right.” I’ve written a number of entries on my blog concerning this story (1, 2, 3, 4). In fact, I even wrote to Reynolds asking him for details regarding the BBC’s presumed verification of the story. He informed me that the BBC’s ‘Arabic-speaking Middle East editor checked the story and had even read the text from the newspaper’. When pressed for further information, Reynolds replied that the BBC’s ‘Arabic-speaking Middle East editor [who had] checked the story and had even read the text from the newspaper’ “was not Jeremy Bowen! We established to our satisfaction that the pictures were printed. If you can show this to be wrong, then good luck to you.” Which I believe is a semi-polite way of saying ‘piss off’.

And all I asked for was some co-operation. Strewth!

2) The Power of Blogs

“The other role of the blogs is to criticise and attack.”

Fair enough. Don’t claim you never asked for it but.

To begin with, the ‘power of blogs’ appears confined to ‘bringing down’ or ‘damaging’ the reputations, even the livelihoods, of journalists and corporate executives, including VIP ‘journalists’ such as Dan Rather and executives such as CNN’s Eason Jordan. As a result, ‘big media should take notice’.

Leaving aside the facts regarding Rather’s presumed embarrassment at the “unravelling” of one of his stories on “60 Minutes Wednesday” and Eason Jordan’s chagrin at being forced to resign as a result of his having made “some remarks at a discussion in Davos in January 2005 about journalists being possibly targeted by US troops”, what does this role of ‘criticising’ and ‘attacking’ involve I wonder?

Well, while Reynolds’ concern for his colleagues in the US is touching, I’d argue that the power of blogs can only be multiplied if one keeps in mind Sylvester’s dancefloor classic “You make me feel mighty real”. Less cryptically, bloggers need to keep it real. And by that I mean delving much deeper into the political economy of the mass media, and responding accordingly.

3) Political agendas

“Of course, one has to remember that most blogs have political agendas. Many of them are on the right of the spectrum. But it is not that hard to discount the opinionating and pick out the facts.”

Huh?

This final section of Reynolds’ article is in some ways the most problematic. That blogs have political agendas is a basic banality; as banal as stating that one has to remember that Paul Reynolds and the BBC too have a “political agenda” (as almost any student of Politics or Media 101 should be able to inform you). This section also concentrates on outlining the views of three right-wing critics of the BBC, as well as one from the left.

Ho-hum.

[Medialens criticised

among others, The Independent [British newspaper]: “The Independent is feeling the heat from public criticism of its adverts pushing foreign travel, cars and endless consumerism.” In fairness, it also quoted an Independent editor who dismissed such critics as “a curmudgeonly lot of puritans, miseries, killjoys, Stalinists and glooms.” So, unlike some sites, it does seek debate.”

Ho ho ho.]

In conclusion, Reynolds notes that

I have taken to intervening in some of these sites if and when I am personally criticised and sometimes to defend the BBC in a general way. Otherwise the comments go unanswered. I found that one rapidly develops a very thick skin and I can now understand how politicians can cope with criticism. If the mainstream media does not respond, it will suffer. The same is even truer of businesses, whose products can be disastrously damaged by web-based attacks.

This appears to be the main motivation for Reynolds’ article: defence of himself as a journalist and of the BBC as a media organisation from ‘attacks’ by bloggers. But the last word goes to

Richard Sambrook, head of the BBC World Service and Global News Division… “The BBC should proactively engage with bloggers. This is a new issue for us. Some departments look at blogs, though haphazardly. But it pays dividends. The BBC is a huge impersonal organisation. It needs to come out from under its rock,” he says. As for using blogs as a source he says: “The key is careful attribution. It would be a big mistake for the [state/corporate media] to try to match the blogs, but they can teach us lessons about openness and honesty. The [state/corporate media] should concentrate on what it can do – explain, analyse and verify.”

“Proactive engagement”.

“Careful attribution”.

“Openness and honesty”.

Explanation. Analysis. Verification.

Or as Reynolds summarises: The ‘mainstream media’ establishes to their own satisfaction that news stories are credible. If you can show this to be wrong, then good luck to you.

(Now piss off.)

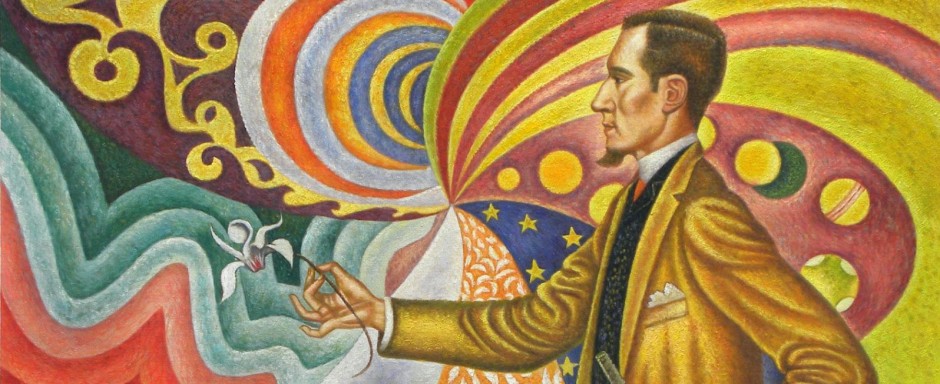

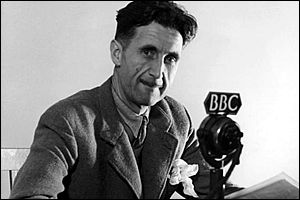

Some things which Orwell experienced at the BBC did eventually prove useful to him when he was able to draw on them for inspiration in the creation of the nightmare bureaucracy of the Ministry of Truth. Compared to this fictional monstrosity, the BBC was as harmless as Orwell implied when he joked that ‘its atmosphere is something halfway between a girls’ school and a lunatic asylum’. But in his time as one of its employees he learned enough about the workings of large organisations to understand how they can create justifications for meaningless activity, and how they can persuade so many of their workers to take this work seriously. And he was reminded of how stultifying it can be to work in an atmosphere where the threat of censorship is ever present. He felt that way in Burma, of course, where a kind of unofficial censorship was imposed by pressure from the empire builders straining under the loads of their white men’s burdens. But it was the routine, institutionalised nature of the censorship at the BBC which Orwell found intriguiging, and depressing.

— Michael Shelden, Orwell : The Authorised Biography, Heinemann, London, 1991, p.380.